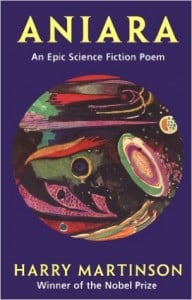

Martinson, H. (1998) Aniara: An Epic Science Fiction Poem. Translated from the Swedish by Klass, S. & Sjoberg, L. USA: Story Line Press.

Cover of Aniara from Sjoberg’s translation

Aniara

1

My first meeting with my Doris beams

with light to make the light itself more fair.

But let me simply say about my first

and just as simple meeting with my Doris

that now it forms a picture all can see

every day before them in all the halls

sluicing refugees to lift-off zones

for urgent excursions to the tundrasphere

these present years, when Earth, become unclean

with toxic radiation, is accorded

a time of calm, repose and quarantine.

She fills in cards, her five small nails a-glint

like dim lamps through the concourse twilight.

She says: Sign your name on this line here,

where the light is pouring down from my blond hair.

She says: You’re asked to keep this card at hand,

and should some danger of the kind that stand

listed here on page two hundred eight

threaten havoc to our time and state,

then you come here and in the space assigned

put down exactly what you have in mind.

The part of Mars where you’d prefer to go,

the tundra east or west, is checked off here.

One jar of uncontaminated soil

is owed by everyone, as stated there.

At least three cubic feet, as sealed by me,

will be recorded for each traveler’s share.

She looks at me with the disdain that beauty

so easily conceives when looking round

at folk on twisted paragraphic crutches

scrambling up and down the steps at lift-off ground.

Off through the fire-exit, numbers more and more

she watches disappear, to new worlds bound.

The monumental foolishness of living

is thus made obvious to one and all

who’d spent years hunting for one crevice giving

access for a gleam of hope to fall

into that hall where processed emigrants

start up each time thev hear

a rocket-siren squall.

2

Goldonder Aniara shuts, the siren gives the wail

for field-egression by the known routine

and then the gyrospinner sets in towing

the goldonder upward to the zenith light,

where magnetrinos blocking field-intensity

soon signal level-zero and field-release occurs.

And like a giant pupa without weight,

vibrationless, Aniara gyrates clear

and free of interference out from Earth.

A purely routine start, no misadventures,

a normal gvromatic field-release.

Who could imagine that this very flight

was doomed to be a space-flight like to none,

which was to sever us from Sun and Earth,

from ‘Mars and Venus and from Dorisvale.

3

A swerve to clear the Hondo asteroid

(herewith proclaimed discovered) took us off our course.

We came too wide of Mars, slipped from its orbit

and, to avoid the field of Jupiter,

we settled on the curve of I.C.E.-twelve

within the Magdalena Field’s external ring;

but, meeting with great swarms of leonids,

we headed farther off to Yko-nine.

In the Field of Sari-sixteen we gave up attempts

to turn around.

As we held our curve, a ring of rocks

echographically gave back a torus-image

whose empty center we sought eagerly.

We found it too, but at such dizzying angles

that the passage to it led to breakdown

of the Saba Unit, which was hit hard by space-stones

and great swarms of space-pebbles.

When the ring had moved off and space had cleared,

turning back was possible no longer.

We lay with nose-cone pointed at the Lyre

nor could any change in course be thought of

We lay in dead space, but to our good fortune

the gravitation-works were still in service,

and heating elements as well as lighting

were not disabled.

Of other apparatus some was damaged

and other parts less damaged could be mended.

Our ill-fate now is irretrievable.

But the mima will hold (we hope) until the end.

4

That was how the solar system closed

its vaulted gateway of the purest crystal

and severed spaceship Aniara’s company

from all the bonds and pledges of the sun.

Thus given over to the shock-stiff void

we spread the call-sign Aniara wide

in glass-clear boundlessness, but picked up nothing.

Though space-vibrations faithfully bore round

our proud Aniara’s last communiqué

on widening rings, in spheres and cupolas

it moved through empty spaces, thrown away.

In anguish sent by us in Aniara

our call-sign faded till it failed: Aniara.

5

The pilots are more nonchalant than we

and fatalists of that most recent stamp

which only vacant spaces could have formed

through seeming-changeless stars’ hypnotic force

on human souls agog for mysteries.

And death fits altogether naturally

into their scheme, a constant crystal-clear.

But still one sees that after five years now

they too look down the pinnacle of fear.

At some unguarded moment, close-regarded

By me who read the features of their faces,

grief can shimmer like a phosphorescence

from their observer-eyes.

It’s seen most clearly in our female Pilot.

She often sits and stares into the mima

and afterward her lovely eyes are altered.

They gather a mysterious sheen

of nebulosity, the iris of the eye

is filled with mournful fires,

a hunger-fire searching after fuel

for spiritual light, lest that light fail.

A year or so ago she once remarked

that, personally, she would be quite willing

for us to polish off death’s bitter pill,

make that our farewell dinner and be gone.

And many must have thought like her—but the passengers

and all the naive emigrants on board

who even now scarce know how waywardly we lie,

to them the Cabin has its bounden duty

and now that Cabin’s duty is eternal.

6

The mima tuned us in to signs of life

spread far and wide.

But where, the mima gives no word of.

We pull in traces, pictures, landscapes, scraps of language

being spoken someplace, only where?

Our faithful Mima

does all she can and searches, searches, searches.

And her electron-works haul in,

electro-lenses give her screener-cells

their coded programs and the focus-works collect

the tacis of the third indifferent webe

and sounds and scents and pictures emanate

out of lavish fluxes.

But where their sources lie she gives no word of.

That lies outside and always far beyond

a mima’s technics and her powers of hauling in.

She fishes metaphorically her fish

in other seas than those we now traverse,

netting metaphorically her cosmic catch

from woods and dales in undiscovered realms.

I tend the mima, calm the emigrants,

cheering them with scenes from far-flung reaches

of things in thousands which no human eye

had ever dreamt of seeing, but the mima tells no lies.

And most do understand: they know, a mima

can’t be bribed, she is all probity.

They know that the mima’s intellectual

and selectronic sharpness in transmission

is three thousand eighty times as great

as mankind’s could attain if it were Mima.

As before an altar they bow down

whenever I come in to start the mima.

And many times I’ve heard them whispering:

Imagine, though, if one could be like Mima.

So it’s to the good that the mirna has no feelings,

that pride has no place in the mima’s insides,

that as from habit she delivers images

and tongues and scents from undiscovered countries

and tends to this unmoved by blandishments,

secured by probity, unstirred by incense.

She takes no notice that in this darkroom

a sect of mima-worshippers bows down,

fondling the mima’s pedestal and praying

the noble mima’s counsel for the journey,

which now has entered on its sixth long year.

Then suddenly I see how all has changed.

How all these people, all these emigrants

are realizing that what once had been

has been and gone. And that the only world

which we are given is this world in Mima.

And while we voyage on toward certain death

in spaces without land and without coasts,

the mima gains the power to soothe all souls

and settle them to quiet and composure

before the final hour that man must always

meet at last, wherever it be lodged.

7

We still pursue the customs formed on Earth

and keep the usages of Dorisvale.

Dividing time into a day and night,

we feign the break of day, the dusk, the sunset.

Though space around us is eternal night

so starry-cold that those who still abide

in Dorisvales have never seen its like,

our hearts have joined with the chronometer

in following the sunrise and the moonrise

and both their settings viewed from Dorisvale,

Now it is summer night, Midsummer night:

the people stav awake hour after hour

In the great assemblv-room thev all are dancing

save those on watch in the infinitude.

Thev’re dancing there until the sun comes up

in Dorisvale. Then smack comes claritv,

the horror that it never did come up,

that life, a dream before in Doric vales,

is even more a dream in Mima’s halls.

And then this ballroom in infinitude

fills with whimperings and human dreams

and open weeping none hides anymore.

Then the dancing stops, the music dies,

the hall is emptied, all move to the mima.

And for a while she can relieve the strain

and rout the memories from the shores of Doris.

For frequentlv the world that Mima shows us

blots out the world remembered and abandoned.

If not, the mima never would have drawn us

and not been worshipped as a holv being,

and no ecstatic women would have stroked

in trembling bliss the dais of the deity.

8

Our soul is spent on dreams, we’re ever rubbing

dream on dream for want of something real,

and each new mummery becomes a ladder

to the latest dream-beset vacuity.

And evervthing far off becomes our home;

indeed, beyond all pales lies our relief—

I share with Dorisvale my every grief,

and longing ceaselessly to sojourn there

itself is health, is artful living here.

Seldom do we take the slightest note

of our majestic wonder of a boat,

and only during sermons at a grave

does this world dawn on us as all we have;

then come a multitude of black thoughts flapping

through these vaults that hold us bound

filled with the echoes of a prior life

and threading an outlandish void of sound.

Then we scurry to the mima to beseech

those comforts we may see but may not reach.

Then thousands mill in an unending flock

through every corridor to Mima’s hall.

Then suddenly we might remember in a flash

that this craft’s length is sixteen thousand feet,

its width three thousand and the population

milling in its vaults eight thousand souls,

that it was built for large-scale emigration,

that this is onlv one ship out of thousands

which all, of like dimensions, like design,

ply the placid routes to Mars and Venus,

that we alone had canted off our course

until one day the ranking astrolobe

informed us that we were no longer lying

in the inner field, but evervthing

that could be done would certainly be done

so life within the outer field would be

a pioneering voyage and a probe,

the farthest so far toward the field beyond.

When afterwards it struck the High Command

that there would never be a turning back

and laws obtaining in the outer field

were different from those in clear control

of placid flight-routines in inner space,

first panic set in, then came apathy

laying between the tempests of despair

its chillv doldrum-world of dead emotion

till the mima, like a soothing friend in need

and filled with specimens of life from other worlds,

to soothe us all unlocked her vision chest.

9

There are in the mima certain features

it had come up with and which function there

in circuitry of such a kind

as human thought has never traveled through.

For example, take the third webe’s action

in the focus-works

and the ninth protator’s kinematic read-out

in the flicker phase before the screener-cell

takes over everything, allots, combines.

The inventor was himself completely dumbstruck

the day he found that one half of the mima

he’d invented lay beyond analysis.

That the mima had invented half herself.

Well, then, as everybody knows, he changed

his title, had the modesty

to realize that once she took full form

she was the superior and he himself

a secondary power, a mimator.

The mimator died, the mima stays alive.

The mimator died, the mima found her style,

progressed in comprehension of herself,

her possibilities, her limitations:

a telegrator without pride, industrious, upright,

a patient seeker, lucid and plain-dealing,

a filter of truth, with no stains of her own.

Who then can show surprise if I, the rigger

and tender of the mima on Aniara,

am moved to see how men and women, blissful

in their faith, fall on their knees to her.

And I pray too when they are at their prayer

that it be true, all this that is occurring,

and that the grace this mima is conferring

is glimpses of the light of perfect grace

that seeks us in the barren house of space.

10

The sterile void of space is terrifying.

Glass-like is the stare encircling us

and the systems of stars hang frozen and still

in the round crystal windows of our ship.

Then is the time to cherish visions in dreams

from Dorisvales and preserve, here in the sea

where no water, where no waves are moving,

everv dream and every rush of feeling.

The smailest sigh is like a gentle wind,

all weeping a fountain, the ship itself a hind

dashing in silence toward the starry Lyre

which, all too far for any human mind

to understand the distances or times,

has not slid one small inch to either side.

Everything looks as if solidified

and frozen to the mount of Everlasting,

like grains of diamond in a crystal sheath

encompassing the very boundlessness

in a massive, radiant hall of utter distance.

But all the words that have been used to death,

misused on mountains and on tracts of water

and landscapes where they never did belong

were drawn on in advances by a race

with no thought that the words which they were wearing down

might at some future date be sorely needed

right where they suited best: right here, on board

this space ship on its way out to the Lyre.

What has been left for us who most have need

of every word answering to limitless

immeasurably far-outlying Hades?

We are compelled to seek out other words

able to shrink and shrivel all to comfort us.

The word for Star has now become indecent,

the low names high for loins and woman’s breast.

The brain is now a shameful body-part,

for Hades harvests us at its behest.

11

A man from High Command stands amid the people

in the great assembly-halls abaft.

He pleads with them not to despair, but view their fate

in the clear light of science. He maintains

that it is not the first time this has happened.

Sixty years ago a large goldonder

with fourteen thousand souls on board was lost,

had instrument-failure heading for Orion

and plunged with rapidly increasing speed

toward Jupiter, got swallowed in its wastelands

and buried in that giant star’s dense husk,

its evil death-quilt of gelid hydrogen

which to a depth of near ten thousand miles

armors that devil-star in helium and cold.

It could have turned out just as badly here.

But we are favored people. We’ve not crashed

on any star or stellar satellite.

Instead we have our trek ahead of us,

a lifelong journey onward to an end

which would have come in any case, and comes.

12

The orchestra plays fancies and we take the floor.

The girl I lead about is hors concours.

Originally she’s from Dorisburg,

but though she’s danced here now for several years

in Aniara’s ballroom she insists

that, far as she’s concerned, she hears

no difference whatsoever in the yurg

they dance here and the one in Dorisburg.

And when we dance the yurg it’s evident

that everything called yurg’s magnificent

when Daisy Doody wriggles in a vurg

and chatters in the slang of Dorisburg:

You’re gamming out and getting vile and snowzy.

But do like me, I never sit and frowzy.

I’m no sleeping chadwick, Daisy pouts,

my pipes are working, I am flamm and gondel,

my date’s a gander and my fate’s a rondel

and wathed in taris, gland in delt and yondel.

And lusty swings the vurg, I’m tempest-tossed—

the grief I’m nursing threatens to be lost

upon this womanchild who, filled with yurg,

slings at Death’s void the slang of Dorisburg.

13

In the sixth year Aniara fared

with undiminished speed toward Lyra’s stars.

The chief astronomer gave the emigrants

a lecture on the depth of outer space.

In his hand he held a splendid bowl of glass:

We’re slowly coming to suspect that the space

we’re traveling through is of a different kind

from what we thought whenever the word “space”

was decked out by our fantasies on Earth.

We’re coming to suspect now that our drift

is even deeper than we first believed,

that knowledge is a blue naiveté

which with the insight needful to the purpose

assumed the mystery to have a structure.

We now suspect that what we say is space

and glassy-clear around Aniara’s hull

is spirit, everlasting and impalpable,

that we are lost in spiritual seas.

Our space-ship Aniara travels on

in something that does not possess a brain-pan

and does not even need the stuff of brains.

She’s traveling on in something that exists

but does not need to take the path of thought.

Through God and Death and Mystery we race

on space-ship Aniara without goal or trace.

O would that we could turn back to our base

now that we realize what our space-ship is:

a little bubble in the glass of Godhead.

I shall relate what I have heard of glass

and then you’ll understand. In any glass

that stands untouched for a sufficient time,

gradually a bubble in the glass will move

infinitely slowly to a different point

in the glazen form, and in a thousand years

the bubble’s made a vovage in its glass.

Similarly, in a boundless space

a gulf the depth of light-years throws its arch

round bubble Aniara on her march.

For though the rate she travels at is great

and much more rapid than the swiftest planet,

her speed as measured by the scale of space

exactly corresponds to that we know

the bubble makes inside this bowl of glass.

Chilled at such certitude, I take flight

out of the mima-hall to the ruddy light

filling the dance-hall and, finding Daisy there,

I seek admission to her womb of hair,

in her savior-arms I beg a tryst

where death’s cold certitude does not exist.

There’s where life remains in Mima’s room;

the Doric valleys live in Daisy’s womb

as in ourselves, no cold or threat to hound us,

we lose track of the spaces that surround us.

14

A sect that’s called the Ticklers has sprung up.

They gather to be tickled and to tickle.

It’s mostly women, but the chiefs are men

and called the Tinkers,

an old word from the pre-goldonder age.

The word is cited in the Blue Archive

and has to do somehow with feeding

in the older manner, and with flames.

More I do not know.

As a child in school, of course I saw

on some occasion natural fire.

It was kindled, I remember, from a piece of wood

which then was shown around, emitting smoke

and some heat too.

When everyone had looked, the wood was dipped in water.

The piquant little flame was quenched,

Wood was a rare material. Had existed

in pre-goldondic times, but later dwindled

steadily through nuclear catastrophes.

It rather moved us, I remember, watching

in a circle as the wood-chunk gave out light.

But that is long ago, ah me, so long.

15

I shut down the mima, walk one round and listen

to the emigrants, the crewmen,

and hear an old space-mariner tell of Nobby,

doubtless the great love of his life:

By normal standards she was hardly pretty,

pale little Nobby, radiation-mangled.

Three times she was branded and came very near

to fluttering away, but was pulled back

with help from gammosal and Tebe-rays.

And after a year or more in dreary wards

of barracks-hospitals on Tundra Two

she took a bargain-fare goldonder home

from Mars to Earth, resuming her assistance

to refugees and regular collections

for people needing help on Mars and Venus.

All Marsfolk needed respite from the tundra-cold;

the Venusfolk, safety from their swampy climate.

Did she wear her health down? Rest assured.

Nonetheless I held her very dear,

my little Nobby, and cannot forget

the scanty moments when we snatched our dreams

on Tundra Two on my rare visits there.

At that time I was just a volunteer

aboard Goldonder Fifteen—name of Max,

an old tramp off the Venus run, converted

for shipping aid and exiles to the tundraball.

The Thirty-second War had just then ended,

Control Plan Three was being closely followed.

You’re all aware how all of that turned out:

new Dick on top, hot times in the cellar

for those who’d voted nay to Dick. The others,

whipped to shape already, got their rucksacks

and were sped on Prison Spacecraft Seven

to three years’ gathering peat on Tundra Nine,

among the worst tundras you could run into

on that slum planet. We went out there once.

But enough of outsides. All the inward changes

that followed with the punch-card age were worse.

The heartlessly hard, the nonsensically gentle

changed places on the punch-cards many times.

With regularity the good in man

was moved to a punch-card hole for cruelty.

In this melancholy jungle of controls

we have to admire the mima, who can order

a chaos of numbers we wish we never knew.

For everyone was playing at least four roles

in political games of specters’ peek-a-boo.

16

Through doors that are forever whirling round

like turnstiles for the torrents of mankind,

some voices rise triumphant from the hum

that blends them all: despair, good faith, high mind.

And there are scattered voices singing songs

of burdens such as mystics might have sung

in seeking incombustibility

from vacant space and from the mima’s visions:

“Soon the time will come of cast-iron and balm

when I may keep intact while fire and cold

consume the forms of life around my calm.

Soon the time will come of cast-iron and balm.”

But on the humming swells, all seek the mima

and cry aloud as at a wailing-wall,

till from lost worlds the mima’s comforts bring

her illustrations of a far-off spring.

The mima caught for us the blessed shore,

shining for hours in full beatitude.

But now the world of blessings is no more,

hurled into a new infinitude.

Among dark shades that splendor has been drowned,

by torrents that no mima can turn round.

And we again are shivering and unsound.

17

The spuriously deep descents you make

to those supposed depths you’d gambled on

are all without the slightest value here

for here there are no depths to undertake.

Here we can follow the descent you make

and see how very far it is, how sheer.

It’s never stunning on the crystal screen

where we can see how your maneuver turns

spiraling back to where you dove before.

Now we believe in your descents no more.

The space-aware makes no dives as a rule,

and if he does dive in the lucid pool

he’s quickly back and puts off happily

what science gave of outdoor finery

for shorter expeditions on this sea.

His business merely was to cast an eye

upon the only cloud in this cold sky,

that long hard cloud made of a white alloy,

luminously painted and standing there

motionless, stiff and still, what though she fare

at a velocity to curl the hair

of those who don’t know of the speeds we muster

as Aniara moves on toward the Lyre cluster.

Once I was sent outside for an inspection

of Mima’s cell-works and, from this direction,

almost eight thousand meters radially,

our Aniara was a magnitude.

From that celestial ocean, stirred, I viewed

our good old craft from Doris come so far

approaching the Lyre from cosmic Zanzibar

with cargo that the tooth of time had chewed.

Ivory of that kind is heaviest of all

as, marked with hard names born of metaphor,

from a hidden world of hostile force

it cruelly bears down on Aniara’s course.

18

Efforts at escape through flights of mind

and slipping back and forth from dream to dream—

such methods were to hand.

With one leg drowned beneath a surge of feeling

the other braced by feeling dead and gone

we’d often stand.

Myself I questioned, but gave no reply

I dreamt myself a life, then lived a lie.

I ranged the universe but passed it by—

for captive on Aniara here was l.

19

Our female pilot steps inside the mima-

chamber. Wordlessly she signals me

How grand she is, how unapproachable.

She wounds you in the way that roses wound,

though not, as has been often said, with thorns.

A rose will always wound you with its rose

and, though the sore may be a briar-scratch,

still more often it may be a wound

from utter beauty, utter burning beauty.

The lovely Doris, in the sixth year now

changed ever more into a distant star,

a sun that like a cinder burns my eye

and stabs its infinitely long gold pin

into my heart across dizzying-bright spaces—

she burned more broadly when she was close by,

but stings more deeply when she’s far away,

I start the mima, take a seat and wait

to see in little time the features brighten

with wondrous alteration on the face

of our fair pilot, frostily withholding

the subtlest modulation of her beauty.

But the mima’s running, making all things clear.

The fair one’s white cheeks brighten instantly

and hotly blush: she fills with heavenly transport

when the mima shows her everything there is

of pleasure inaccessible in worlds of space.

She smiles, she laughs, ecstatic and engrossed

as though she suddenly were seized by gods.

But just when she seems cleared for perfect bliss

the third webe shifts the mima’s focus-values

and the world’s other glimmering guises flood the mima.

The fair one’s face soon turns another shade.

I close down the mima. It is there for comfort,

not for making human beings shudder

at worlds like-featured with the one they left.

Pains and problems we were all enmeshed in

when we were stirring in the Dorisvales

are nothing to exhibit to this woman.

I stroke her softly when I close the mima,

for the mima’s truth is incorruptible,

a frank display of everything created.

The fair one rises up and nods to me

her sober thanks for closing down the mima.

At the door she turns, asks me to call

for her should the mima ever have received—

she doesn’t say the word, but I can guess.

The warming Doris and the kindly Doris,

the distant Doris now a noble star

to pine for

Now she is the star of stars.

O could I but know where she is gleaming

in this sixth year, so inconspicuous

among the suns of space I’ll never find

that star again. The noble star of Doris.

20

All that we had long dreamt of receiving—

distant views of torments gone before

and joys exhausted long ago—we take

in the mima from the troughs of waves of yore.

The picture shifts in ripples far remote

and in a cryptic echo-curve it’s hurled

labyrinthine round the endless world,

and all the cosmic tidings reach us all.

Through space the evil tidings ever stream;

there are good tidings, but with tracks less clear,

for goodness has no part in active life,

its light is the same light

this year and every year.

21

But doubt is an acid that corrodes more dreams

than any dreamer ever could propose,

and only through the mima can we see again

the warmth and beauty of our dreaming-shows.

For this reason I preserve what matters:

what bears comfort’s colors and resembles life.

And on our ship, whenever anxiety patters

and dread and unease play havoc with our nerves

I serve up helpings of the mima’s dream-preserves.

22

Meanwhile the doctor who observes our eyes

and sees in them that lust for life is fading

flinches at the lacus lacrimalis

where no more does the crocodile go wading.

Such flooding tears in halls where Mima reigns

are highest praise for Doris’s green plains.

And even so it is as if those tears

for all their authenticity were cold

insensate waters rising from the depths.

Their fall is too transparently designed,

like drops of rain too pure to touch the soil:

our lucid tears in an Aniara of the mind.

23

The senior astrolobe came to our aid,

expert in the blazes far stars made.

But, without warning, reason’s star went dead

inside the senior astrolobe’s own head.

Forced to its death by bodings unallayed,

his brain broke down and died, soul-deep afraid.

24

Impotence runs wild in its own way,

blaspheming, execrating time and space.

But many think that now we’ve come to face

just punishment as toward the Lyre we pace.

For we ourselves by space-law rigorous

have locked us into this sarcophagus

and honor our live burial on high

till our vainglory puts its scepter by.

In thousands or in myriads of years

a distant sun shall capture and enfold

a moth that flies toward it as toward the lamp

when it was harvest time in Doriswold.

Then we shall end our journey through these regions,

then deep asleep shall lie Aniara’s legions

and all be swiftly changed in Mima’s hold.

25

We ride in our sarcophagus in silence,

no longer offering the planet violence

or spreading deathlv quiet on our kind.

Here we can question freely, true

while the vessel Aniara, gone askew

in bleak tracts of space, leaves vile time behind.

26

The stone-dumb deaf man started to describe

the worst sound he had heard. It was past hearing.

Though just when his eardrums were exploding

came a sound like the sough of sorrowing sedge, the last

when the phototurb exploded Dorisburg.

It was past hearing, so the deaf man ended.

My ear could not keep up with it

when mv soul burst and scattered

and body burst and shattered

and ten square miles of city ground were wrung

inside outside

as the phototurb was bursting

the mighty city once called Dorisburg.

So he spoke, the deaf man, who was dead.

But as, so it’s been said, stones shall cry out,

so the dead man did his speaking in a stone.

From the stone he cried out: can you hear me?

From the stone he cried out: don’t you hear me?

My native city once was Dorisburg.

Then the blind man started his report

upon the light horrificallv intense

that blinded him.

He was unable to describe it.

He mentioned only one detail: he saw by neck.

His entire skull became an eye

blinded by a brightness beyond flashpoint

lifted and sped off in blind reliance

on the sleep of death. But no sleep came.

In this respect he is much like the deaf man.

And as, so it’s been said, stones shall cry out,

so he cries out from stones as does the deaf man.

So they cry out from stones one with the other

So they cry out from stones as did Cassandra.

I rush in to the mima as though I could

prevent the ghastly deed by my distress.

But she shows all, candid and upright,

unto the last projecting fire and death,

and, turning to the others, I cry out

my pain of pains beholding Doris’s death:

There is protection from near everything,

from fire and damages by storm and frost,

oh, add whichever blows may come to mind.

But there is no protection from mankind.

When there is need, none sees with clarity.

No, only when the task is to beat down

When there is need, none sees with clarity.

No, only when the task is to beat down

and desolate the heart’s own treasury

of dreams to live upon in cold and evil years.

Then the mima’s blinded by a bluish bolt

and I am dumbstruck at events that pour

on wretched Earth; out here their lightnings bore

down through my heart as through an open sore.

And I the mima’s faithful priest in blue

receive in blood run cold the evil news

that Doris died in far-off Dorisburg.

27

My only comfort left I beg of Daisy.

She is the only woman left who speaks

that lovely Dorisburgian, while I’m

the last man left who understands what Daisy

with her splendid tongue, bright as a decoy-call,

babbles in her lovely dialect.

Come rock me loose and fancy, Daisy wheedles.

Go dorm tremenzy and go row me dondel:

my date’s a gander, I am flamm and gondel

and wathed in taris, gland in delt and yondel.

And I who know that Dorisburg was razed

to nothing ever after by the phototurb,

I let Daisy be just what she is.

What use is there in breaking the enchantment

which only Daisy kept up, unawares,

so well that she, now lying free of cares

and squirming hotly when the dance is done,

knows not that she herself some hours ago

was widowed of the town of Dorisburg.

She urges me to sing along, and I take up

the ballad of cast-iron that I learned

about the town of Gond that melted down in war.

But Daisy babbles gladly, unawares,

and her entire existence was created

to sing the praise of dance in whirling yurgs.

What would I be? A brute, if I should break

the spirited enchantment she has mined

from out her breast, from her heart itching for joy.

She babbles as in fever till she sleeps.

Round where we lie Aniara’s senses fade,

but not to sleep. The clear mind is alert

to Earth which here it has to do without.

Only Daisy’s heart beats safe and sound

on Aniara, to its brightmare bound.

28

With Dorisburg molten, the mima ailed for days

with heavy static from the phototurb,

her third webe battling as against a cloud

of distant compact shame. Upon the third day

the mima begged deliverance from her vision.

The föurth day she had some advice to give me

on the scanner-transpodes in her cantor-works.

Only on the fifth day did her calm return,

upon transmissions from a better world,

and once again her cell-works lit up brightly—

all her strength appeared to be reviving.

But on the seventh day there came a drone

out of her cell-works I had never heard.

Indifferent tacis of webe number three

switched off, reporting they’d gone blind.

And suddenly the mima called me forth

to her inner barrier and, trembling,

I went to stand before her awesomeness.

And when I stood there, moved, cold with fright

and filled with worry for her situation,

all of a sudden her phonoglobe began

talking to me in the dialect

of higher ultramodern tensor-theory

which commonly we’d use on working days.

She bade me tell the High Command that she

for some time had been just as nice of conscience

as the stones were. She had heard them cry

their stonely cries in distant Dorisvale.

She had beheld the granite’s white-hot weeping

when stone and ore were vaporized to mist.

She’d been much troubled by those stones’ travail.

Darkened in her cell-works by the cruelty

man exhibits in his time of sin

she came now to the long expected phase

(which mimas reach) of finally decaying.

The indifferent tacis of webe number three

see a thousand things that no eyes see.

Now, in the name of Things, she wanted peace.

Now she would be done with her displays.

29

But it was all too late: I could not stop

the people crowding toward the mima hall.

I cried, I screamed to them to turn about,

but no one listened, for, although they all

wished, horrified, to flee that mimadrome,

they moved on, mad to watch what things would come.

A bolt-blue light flashed from the mima’s screens;

across the Mima’s halls a rumbling rolled

like booming thunder back in Doriswold.

A jolt of terror pitched into our horde,

and many emigrants were stomped to bits

when Mima perished on Aniara deep in space.

The final word she broadcast was a message

from one who called himself the Detonee.

She had the Detonee himself bear witness

and, stammering and detonated, tell

how grim it always is, one’s detonation,

how time speeds up to win its prolongation.

Upon life’s outcry time does increase speed,

prolongs the very second when you burst.

How terror blasts inward,

how horror blasts outward.

How grim it always is, one’s detonation.

30

Now came a time of bitterest discontent

and long I sat there silently to ponder

in the Mima hall where evil sent

its storm of dark rays from the back of yonder.

Franticallv I sought to activate

our hallowed Mima’s comfort-works and art

and with the tensorides to operate

the hub of marvels at her godly heart.

The voice inside the phonoglobe was still,

and what few calls the sensostat could find

came from a Boeotian shade, so imbecile

it fell below both god and humankind.

And, further, I was pinned down by the pack

hounding me and heaping me with scorn,

while I was weighed down in my cul-de-sac

by all my heart’s calamities far-borne.

And Chefone, the fierce lord of our craft,

would enter every day to vilify me

and, though his schadenfreude plainly showed,

his threat was merely that a court would try me.

He often sought through mystic rigmaroles

to magnify his station in our caravel

and uttered devil-dictums to our souls

to make us think that we were bound for Hell.

By such means day by day he did quite well,

and, buttressed by that specter-like infinity,

he struck you as a man out to compel

his people to decline and asininity.

31

Chefone now ordered persecutions,

and I and many others were secreted

in shelters farthest down in the goldonder

until the bowls of fury were depleted.

There sat technicians trained in each pursuit

involved in the Fourth Tensor repertory,

whereas all those who ceaselessly pollute

pure intellection wrapped themselves in glory.

In endless muddle people sought to prove

the mima’s tragedy was our misdeed,

for all our egos had defiled her screen

with private thoughts which made her sights recede

and dirtied comfort’s flood with private dreams

and dimmed her radiance, her cosmic streams.

Protesting we were innocent, we sought

to reason without learned reference

and in the language most of them were taught

propound the barest modicum of sense.

But this same language, meant to clear up all,

grew murky for us too, a blind-man’s buff

of words avoiding words and playing blind

amid the clarity of cosmic mind.

We then tried drawing for them as for brutes

and savage tribesmen such as were, books say,

alive in that great age which constitutes

the lowest reach of time in spirit’s day.

We drew signs representing plants and trees,

we sketched a many-tributaried flood,

Building texts up by these strategies

which, with the pictures’ aid, they faintly understood.

For us too these were alien inflections

in language far from cybernetic land,

so that we made small sense of the directions

whereby we meant to lend a helping hand.

The upshot was, this court of arbitration

which might have freed us from the doom of space,

was of a hundred minds in its opinion

while the bridge between us stayed an empty place.

32

By systematic logostylic sounding

of Mima’s language-cycles phase by phase,

in two years’ time I’d won so good a grounding

in how to see through all things as through glass

that three years from the very day I saw

Mima burst apart in Aniara’s hall

I plumbed the transtomizers for the law

which predetertmines what shall rise or fall.

And, finding it, I went almost insane.

A dreadful-drunken, deeply unreal glee

at once transformed my soul to space and eye

within the dwelling of infinity.

Then I was taken from the bottom jail

—our female pilot too sat in those cells,—

back into the holy mima’s halls.

And rumor ran. I heard the joyful yells.

And all spoke of the treasure brought to light,

and Mima come back in the starry night.

33

Too quickly I rejoiced in Mima’s hall:

on each solution a mystery waits to leap.

I saw the key now, but as through a wall

of space-clear glass and crystal sheaths miles deep.

Without the mima, by whom I’d been sustained,

in spirit undernourished, I was teetering,

the mind’s blood, in my shock, was being drained.

Bereft of Mima, I found petering

and dying at her base a mirror-world.

Slumped by her remains, as by charred brands,

I gazed into her breast and saw a hearth grown cold.

34

Myself, I have no name. I am of Mima

and so am called no more than mimarobe.

The oath I swore is called the goldondeva.

The name I’d borne was cancelled at “last rounds”

and had to be forgotten ever after.

As for Isagel, our female pilot,

the matter of it is that her position

establishes her name, which is a code word.

The inmost name she bears and which she whispered

close against my ear I may not breathe.

In her eyes there is an inaccessible

but yet a lovely glow of things unspoken:

the radiance which enigma oftentimes possesses

when it’s the beauty of the mystery that impresses.

She draws curved lines, her nails are glowing

like feeble lamplights through the chamber’s dusk.

She tells me: Take a reading of this arc

where the shadow of my sorrow sheds its dark.

She rises then to leave her gopta-board,

and over me her radiant thoughts are poured.

And our eyes meet and lock, and soul to soul

we stand, unspeaking. Isagel I love heartwhole.

35

But the rigors of space impel us into rites

and altar-services we’d scarce performed

since pre-goldondic times now half-forgot.

And Aniara’s four religious forms

with priesthood, temple-bells and crucifixes,

vagina-cult and shouting yurgher-girls

and tickler-sectaries forever laughing

appear in space, jostling one another

for the eerie deserts of eternity.

And I in service as the mimarobe,

responsible for all the burst illusions,

must make room in Mima’s sanctuary

and blend all spectacles and all their sounds

when libidine dances with voluptuary

to ring in their god by orgiastic rounds.

36

The women have made themselves a lovely sight

—the pains that many had to take were slight.

There Yaalk astir, a dormifid yurghine

with amatory powers at their height,

and there stands Libidel from Venus’ green

and ever-pullulating jungle spring.

And up against Chebeba yurg-enamored,

an ornament from Kandy on her thigh,

stands dormi-juno Gena, round whom clamor

the novice flock on whom she keeps an eye.

For some time I was buoyed up by a plan:

have a thousand mirrors put in place

to give us everything that mirrors can

by their reflections—falsely widened space

which optically can stretch out every inch

eight thousand inches’ worth of false dimension.

When twenty halls were furnished door to door

with mirrors we had taken from fourscore

the end result of this was so top-hole

that I for four years by these looking-glasses

wholly beguiled the shivering of soul.

To train our eves from our trajectory

and on the multi-mirrored world of gaietv

I turned so many minds to the carouse

my mirrors offered in the mirror-house

that even I myself took time to vurg

with Daisv Doodv out of Dorisburg.

But also with Chebeba and with Yaal

mv mirror-image swung in Mina’s hall.

They come in flock by flock, I see them waken

to yurgs and cults and I look on admiring

where they, by vurgs among the mirrors shaken,

are by octupled mirrors overtaken.

From all sides where the yurghing circles round

they view themselves as heaven’s host in dance

reflected in an eightfold radiance,

for Chebeba eight times as for Yaal

and Gena too in an octupled hall.

There’s Libidella with her expert hand

stirring up a man from Dorisland.

And there’s Chebeba in a yurghic ring

whirling toward the mirrors’ Not-a-thing

where dance eightfold Chebebas to and fro

with breasts and feet repeatedlv on show.

Each object yields up all it can of show

when mirror legs and mirror dances go

and in the yurghing-hall those shows blaze trails

to mirror canyons and to mirror vales.

37

Desire and piety crowd into one place,

in rolls the chariot drawn on by a brace

composed of men and women of the cult.

The chilly stave held up by Isagel

is lifted while with cultic lantern Libidel,

augustly followed by eight libidines,

assumes position, lying down to please.

And when they have been warmed by pelvic fire,

all Iying happy, sleepily at ease,

Isagel comes forth with lowered stave

and touches with her lamp three times for luck

our reliquary, blessed Mima’s grave.

There comes a sough like river reeds when Yaal,

her bosom peaceful, sated in her needs,

pauses at the saintly vault and pleads

in gentle whispers to the deity’s bier.

And what deep peace around her features plays

when swells the holy hymn of “Day of Days,”

and Isagel and Libidel and Heba

form the graveside chorus with Chebeba.

38

Behind the mima-hall fair Libidel sat

one winter’s evening, making herself up,

wearing a thigh-bell and a buddha-cat:

a mirrored brooch clamped by her navel-cup.

A heart gleamed in the charm-pit of her breasts,

which served to warm the precious mirror-gem;

these had an inky field around their crests

for when the thyrsus light would fall on them.

Closing in on her in expectation,

her secret rivals purred their panther hymn

while poised to devastate her reputation

and twist it till her charms had all grown dim.

She still was fair of form and led the gambols

in the Cult’s den, but there would come days

when her bikiniette more showed the shambles

of her curves than sparked her devotes.

Already she’d begun to hide from view

prospects but an inch from sacred places

and round-the-hip Xinombran fabric drew

one’s eyes away from physical disgraces.

But many adepts, once her votaries,

in secrecy were ripening their doubt,

not crowding in as once to seek their ease

upon her lap when she was leading the devout.

A-tremble Libidel adjusts her hair.

To her the navel-brooch feels like a wound

but still she hopes her breasts, an ample pair,

in fellowship with two alluring thighs

will mean for her another year’s survival

at altar-height, though autumn prophesies

already, with grim portents, its arrival.

In sun-red sarathasm and plyelle

the luscious Yaal is standing by her side—

till her year comes she’s young enough to bide,

the year when she herself will be the belle

one night of falling stars, succeeding Libidel.

39

A breakthrough which had never been foreseen

was made by Isagel, our female pilot.

One morning she sat silent in the Gopta room

where she was occupied with Jender curves.

Thereupon she called me to the Jenderboard,

where lightning-swift she’d stabilized her breakthrough

provisionally in its final form.

She shrieked with gladness, hugging to her heart

the vigorously kicking inspiration

which, born of her, was joyously conceived

in deep love for the Law of Aleph Numbers.

And, studying the child, I plainly saw

that it was sound and had the model health

which always had distinguished Isagel,

the faithful servant on the farm of numbers.

Such a breakthrough made in Doric valleys,

had the Doric valleys still remained

a passable abode for number artists,

would at once have markedly expanded

and changed profoundly all of Gopta science.

But here where we were fated to the course

dictated by the law of conic section,

here her breakthrough never could become

in any manner fruitful, just a theorem

which Isagel superbly formulated

but which was doomed to join us going out

ever farther to the Lyre and then to vanish.

And as we sat there speaking with each other

about the possibilities that now stood open

if only we weren’t sitting here in space

like captives to the void in which we fell,

we both grew sorrowful but kept as well

the joy in pure ideas, the kind of pleasure

which together we could share in quiet

for the time still left to our existence.

But Isagel at times burst into tears

to think of the inscrutably great space

with room for all to fall eternally—

as she herself now, with the unlocked mystery

she’d neatly solved, but which was falling with her.

40

THE SPACE-HAND’S TALE

The transfer out to Tundra Three took up nine years.

Evacuation Gond took up ten years.

I myself was on the eighth goldonder.

We alternated with some other space-ships,

Benares, Canton, Gond and others still.

In five years we took something like three million

frightened people to their current star.

The memories still feel like tender wounds.

mainly visions of the lift-off zone,

time after time the same unruly scene

where tears and gnashing teeth mix merrily

with cheerful songs from space-cadets, still green.

When that day’s group of Gondians, each one

with punch-card passport and an I.D. pin,

are led forth to escape Earth’s shame and sin,

they still recoil at the departure time,

but by their very numbers they’re squeezed in

ever nearer the goldonder’s holding-pen,

where several hardened Venus-going men,

their eyes lit by that star, examine them

and wisecrack: Welcome home, ahem, ahem,

to Heaven’s kingdom from Jerusalem.

Fast talking brings disquiet under control

until each punch-card matches with the soul

identified by prior testing; in

it goes to microrolls at rapid-spin

which make a note of every loss and win.

Then, lifted up into the cosmic field,

they reach the tundra kingdom to be steeled.

But others go to Venus’ marshy shore.

We know what both locations have in store,

In murkv mines they shut up all the nations

used and misused like things without a soul

till finally the rejects are expelled

into the Chambers over at Ygol.

Incomprehensible this cruelty.

No image can conceivably describe it:

with cold official headsmen serving daily

at spigots, bolts, and circuit-switches.

And glass-equipped surveilliance-ducts

into the Chambers

at whose outer walls the death-attendants,

their blinking held in check and they unmoved,

peer in with cold satanic eyes, following

the captives’ battles

with the stonework wall.

On, soul (too late to balk at memories),

to Tundra Two, where stands the plexi-housing,

where I with Nobby hoped to go out browsing

in Martian spring, contamination-free.

There proudly those black frigitulips grow,

tempered to the planetary freeze,

and through the tundra comes the Cock’s hoarse crow

to claim the tundra’s few amenities.

Widely worshipped, though sadly starved and gaunt,

what doesn’t that bird know of cold and want!

Else, only arctic willows prosper there,

—if we may pause now at the vegetation—

trailing camellia-like, hard as ironware,

and blackened leaves well nigh inedible:

fitly toughened for this frozen plain,

digested only by the Cock whose craw

employs a set of stomachs in a chain.

When on such leaves as these he stuffs his gut

it’s as though you listened to the last bolt shut

on life’s capacity for pulling through.

For all you see then is the endmost craw

clicking like a lock, and, when it swallows,

transfixed and shuddering the viewer follows,

though in the same breath he’ll be laughing too.

To this terrain of starkest, plainest forms,

Nobby yet was bound with all her soul,

for bitter years of want bring other norms

than those when nature is in full control.

In these last rations of the Martian cold

she found in sighing willows music greatly-souled.

She walked the heaths and sang about the spring

when the Cock was crowing and the thaw begun

and round the tundras went the willows creeping

in hungry stretches toward a half-size sun.

She often sent off willow-leaves to Earth

and wrote: These leaves are from the spirit’s wood

and on the soul’s moors the winds of spring are blowing.

My heart is filling; yes, you’ve understood.

It was the evil time when Gond in the flame

from the phototurb was twisted to a spiral,

a swirling pillar made of torrid gases,

a migrant city crossing Dorisvale.

Compared to that the superchilled clear air

of Tundra Two was much to be preferred,

and the figure of the Cockerel, gaunt and spare,

became transformed into a bright Bluebird.

Nobby’s pleasure in the Tundra’s breath

makes perfect sense against that land of death.

Indeed, this was a masterstroke of hers,

that she got something out of all these things

so quickly counted. I believe there were

no more than ten life-forms the whole sphere over.

Observe her walks among the prison barracks

and the grimness of the men when in a grisly knot,

wolfishly starved, uncovering the pot,

they flocked to eat the Martian in its stock,

the skinny and unstewably tough Cock

no tundra-cook could tenderize one jot.

But Nobby was a girl unlike the rest.

She saw no point in rising to protest

to men who’d shortly lie concealed in tundra-rind

and just as shortly slip the bondsmen’s mind.

The life she lived appeared cartoonish, crude,

in the mirror that displayed her days and ways,

nor had she the style to seem less rude—

and scarcely bettered by the somber gaze

each prisoner afraid and shaken would rest

on that mirror where the truth must be confessed.

I love to linger at the dear remembrance

of such a woman who shared all things known

back then as suffering and sacrifice,

though now their names have a much colder tone.

When altars grew too worn with blood collected

the sacred fell away, so one suspected.

It was the last spring nature was alive.

That springtime nature perished of a wind

that plunged at typhoon strength among the mountains

and with its thunder filled the land of Rind.

A sunroar came, the lightnings ramified.

I still hear the screams and screeches—Sombra! sombra!—

from souls already blinded and afraid

and rushing out to God in search of coolness.

They did not know God too was in the fire

of matter which, combusted and befouled,

with flame primordial chastised Xinombra.

The giant force of the external grew.

The unimaginable years set in

when all was inundation from without.

Though souls were trying hard to hold their own

with what inheritance they had within,

the giant torrent took them one by one.

The mental image of their destiny

that torrent shattered and made meaningless;

the drama that was them just previously

was outflanked by a loose, but nonetheless

unyielding deluge of enfeeblement.

They shattered into cellules in a State

which made claims on them as it used to do,

no matter that it just had melted down

the psychic structure held to be its due.

So mankind knew, upon its sentencing

to deportation out on Tundra Two,

nought, nothing, of the nature of its crime

but much more of the giant’s cruel claim.

And even more about the brutal time

it went to serve within a quarry’s jaws

and in a towering transparent keep,

with rational surveillance as its cause,

spun round the edges of the cesium quarry

at Antalex, in Penal Territory.

God’s Kingdom was not of a world that hard

and grew still less so every passing year,

and those who could ascended heavenward

with bodies first, although their souls stayed here.

You could observe how many muckamucks

broke camp from Rindish vales when time grew late.

And we had fistfights with some rowdy bucks

and roughnecks crashing the goldonder gate.

The pious should have stood up to those bucks,

of course, and bared their teeth to make them cease.

Their peacefulness was overdone; the roughnecks

changed it very quickly to eternal peace.

The unresisting souls on all our lands

died complaisantly of those rough bands.

The shyly fearful and the deeply tactful

were left back in a gamma-lethal glen

and maec tor Heaven in some other way.

They never entered into Milna’s den.

Of such things I as space-hand can report,

who nearly thirty years have plied the spaces

between Earth’s ball and that bare pate of tundra,

Such an occupation leaves its traces.

With time we all have something to relate

that doesn’t come from daydreams in the skies.

And without Nobby there to compensate,

would life be anything a man could prize?

For Tundra captives she had cleaned and sewn

and gone without, all for the love of man.

And but for me you never would have known

the tale of Nobia the Samaritan.

41 THE INFANT

Chebeba was sitting in her finest year

with boundless joy beside the little bier.

Upon the bier there lay the buttercup

she had protected against growing up

in Aniara-town.

In came Yaal then in her finest year.

She saw the infant dead upon its bier

and spoke up in a harsh and ringing voice:

You’re going home. But we stay, not by choice,

in Aniara-town.

And Gena came as well. And Gena said:

To you, my child, in worship I am led.

I don’t dissemble. I have full respect

for you who went to sleep without defect

in Aniara-town.

Yaal slipped away and Heba took her place.

She could not speak, could only turn her face

and on the poised and settled infant gaze,

asleep, afloat into the day of days

from Aniara-town.

42 LIBIDEL’S SONG AT THE MIRROR

My life is in a funny place.

Come here and look and touch it too.

And if you plead and give with grace

my little life belongs to you.

Your gallop under Lyre’s cluster

will make a memory when it’s through.

Life dwells in folds of silken luster,

that little life that’s best with you.

Rider from the Lyre so wild,

tap at my door for a rendezvous.

With your seed I’ll grow with child

in that little life that’s best with you.

It’s staring. Staring cold outside.

Come in, I’ll bring some warmth to you.

Suppose that in our arms cold died,

O, what hot thinking in the blue.

Then Libidel would be admired,

not smeared as now she is by swine.

Behold my body, how desired

it’s been in words and in design.

43

In Mima’s time we were arena ghouls,

who all crowded around Mima and elected

to see and hear, risk-free, all she projected

of pain and struggle upon Gondish ground

and who, when our excitement found release

and in our mouths we marked the taste of blood,

made the mima-tender switch the channels,

alter range, and make the next go-round

show something else. And so our bill of fare

proved a well-balanced diet, as an evening’s death

alternating with a joyful dawn

dismissed the questions flung out in distress

and torment by some far-off settlement.

This equalizing factor then appeared

as something to the good, and Gond was found

a land which, having once seen better days,

was ripe for evil now to have its round.

Harnessing that eye of probity

we felt ourselves Xinombrian sensations

as we, amid our journeyings on high,

converted others’ pains to views and music.

And although Mima for Xinombra’s ill

no less than Dorisburg’s was seen to quaver,

we loved to trail those victims to the kill,

hyenas granted the hyena-favor

of risk-free presence when the lion springs

and power to shrug off conscience when it stings.

The number of butcheries we thus beheld,

the number of see-saw battles we were in,

is legion. We would look upon the felled

lying prone and still, but then rushed past

to be in on it when the next wave swelled.

The faithful mima relayed all of it

with steadfast clarity and no redactions.

And even if sometimes we might well sit

rigid and repelled bv many actions,

still these actions were so very many

that memory could preserve only the worst.

These we named the Peaks, and put out of mind

the gulfs to which the others were consigned.

44

In Chamber Seven are the files of Thinking.

Very few visitors. Still, they have things there

that merit being thought of times on end.

There stands a gentleman called the Friend of Thought,

giving everyone who’s so inclined

the fundamentals of the laws of mind.

He points in sadness to a crowd of thoughts

which might have saved us were they timely set

to work upon the soul’s development

but which, since soul was not much evident,

were hung up in oblivion’s cabinet.

But as our days of vacancy would drag

someone always came here and besought

a look at this or that old line of thought

which, given a new twist, might briefly snag

new interest until that too would flag.

45

The Calculator running all the time

to calculate our minimum of hope

outpaces all our flights of thought

and pulverizes objects of our thought

so comically that on perfection’s ice

the very act of thinking takes a spill.

Then the brain laughs out the way brains will,

a snob exposed in slipperiness of mind,

a mental brute now totally hemmed in

by the quotients of the calculator-works.

A shrug inherited from former days

is all he’s up to: mind’s icy sneer

of bitter barrenness, a world-grimace.

46

We listen daily to the sonic coins

provided every one of us and played

through the Finger-singer worn on the left hand.

We trade coins of diverse denominations:

and all of them play all that they contain

and though a dyma scarcely weighs one grain

it plays out like a cricket on each hand

blanching here in this distraction-land.

Through the Finger-singers in our rings

we keep some slight connectedness with things.

And now the goster-pieces play their rondies

and now the rindel-pieces pipe their gondies.

Her hand held tight against her lovely cheek

and Finger-singer pressing her ear’s tip,

Heba listens to a dyma-coin,

but flinches suddenly and switches dreams

upon her Finger-singer: sudden streams

of yurghing pleasure captivate her ear.

I asked her, after finishing my round,

Why did vou flinch? And she replied:

I picked up calls for help and pleas for mercy.

‘Ehis coin is carrying a scream from Gond.

47

A number-group philosopher and mystic

of the aleph-number school comes often

with filled-in query-card to feed the Gopta-works,

bows silentlv to Isagel the bright

and tiptoes down Aniara out of sight.

And Isagel, who finds the questions reasoned,

takes in his flock of formulas and codes them

for the Gopta-boar& third thought-position.

And when she has transformed the number-sets

and gopted carefully the tensor modes

she takes them over to the Gopta-cart

to which she hitches space-assistant Robert,

our brains-trust’s loyal dray for number-loads.

When our numerosopher returns

Isagel must tell him how the land lies:

despite all Robert’s unremitting tries,

on what he asked no Gopta can advise.

The question dealt with “rate of miracle”

in the Cosmos mathematically conceived.

It seems to coincide so much with chance

that chance and miracle must have one source;

one answer seems to do for either force.

And Dr. Quantity (we use that phrase)

makes a silent bow, resigned to grief,

and tiptoes down Aniara’s passageways.

48

A poetess arose within our world

with songs so beautiful they lifted us

beyond ourselves, on high to spirit’s day.

She blazoned our confinement gold with fire

and sent the heavens to the heart’s abode,

changing every word from smoke to splendor.

She was a native of the land of Rind,

and Rindi myths enveloping her life

collectively became a sacred wine.

She herself was blind. From birth, a child

of nights in thousands with no glimpse of day,

but those blind eves of hers appeared to be

a dark well’s floor, the pupil of all song.

The miracle that she had brought with her

was human soulplay on the soul of words,

the visionary’s play on weal and woe.

And we were silenced by the holiness

and we were blinded by the loveliness

in spaces bottomless where we would hark

to Songs of Rind she made up in the dark.

49 THE BLIND WOMAN

The lengthy way I’ve traveled here

from Rind to these environs

is night in color like the way

I took in Rind.

Dark as before. As always.

But the dark turned cooler.

That was where the change lay.

All tolerable dark abandoned me

and to my temples

and to my bosom, kindred to the spring,

cold darkness came and settled in

forever.

A dismal rushing in the Rindic aspen

rattled in the night. I started shivering.

It was autumn. They talked of the maples ablaze,

the sunset in a valley not far distant.

It was described as red

with gleaming spokes and evening-purple.

And facing it the forest stood, they said,

flaring against the night.

They mentioned too the shade beneath the trees

ever whiter with the coming of the frost

as if its grass had been the summer’s hair

quickly aging.

This is how it was described to me:

a backdrop of a fresh-frost white on gold

that flamed up when the summer paid in full

its debt to the collection-agent, cold.

And autumn’s grand excesses were described:

all golden things cast into summer’s grate.

The splendor spread before us, so they said,

was like a funeral in gypsy style:

its mustering of red and yellow cloths

and golden banderoles from Ispahan.

But I stood cold and silent in that dark,

only hearing everything I loved

vanish in a dark and icy wind

and the aspens’ final rattling told

that soon the summer would lie dead in Rind.

The wind then shifted round

and in the night

came the black and terrifying heat.

I fell into the arms of someone

running toward me.

And this someone frightened me.

How could I know in that hot darkness

who it was

that caught me as I fell, embraced me.

If it was a devil or a person.

Because the roaring grew, the hot wind swelled

into a hurricane,

and he who held me cried out ever louder,

yet in a voice that seemed so far away:

Shield your eyes. It’s coming. You’ll be blinded.

Then I made my voice as piercing as I could

and shrieked in answer: I am blind

and therefore shielded. I have never seen,

but always only felt the land of Rind.

Then he released me, running for his life,

where I don’t know, in the dark’s hot roar

outvoiced only by a sudden burst

of fearsome thunderclaps from far away

rolling in my direction, and I blind.

Then down I fell again and set off creeping.

I crept the forests of the land of Rind.

I succeeded in reaching a hollow in the rocks

where the trees weren’t falling, the heat was not intense.

There I lay, happy almost, amid rocks

and prayed god Rind for help and for my soul’s defense.

And someone from the roar entered the hollow

(O miracle)

and bore me to a van with closed compartments

and someone transported me all through the night

to Rindon airfield

where a refugee-agent, silenced

by a voice shout-shattered, hoarsely wheezed

my number and my name and bade me join

the current bound for the goldonder-sluice.

The years that followed were my destiny,

On the Martian tundra I learned how,

like an envoy sent from Rind, to move the guard

with sad songs for a destiny so hard.

I learned to read the braille of mighty screams

in faces which I felt of with my’ hand.

It was as songstress for” Reclaim the Tundra”

that later I would go back to my land.

It was cold there now, all plantlife injured.

But stubborn wills persisted in their plan

to save the soil by means of a new substance

science had discovered: geosan.

How that would come about I can’t explain,

and many said the idea would misfire.

“What none could do, but everyone’s desire”

the plan was called in common conversation.

So I up and left my home and inspiration

for my songs about the land of Rind and sought

the post of singer, serving Chamber Three.

I’m there now, singing “Ah the Dale, ah me!”

and “Little Bird out in the Rosewoods Yonder.”

But also “The Cast-Iron Song” a Gonder

sings so often here in our goldonder.

All struggling for heaven is a struggling for joy

and the aim of every heart is paradise.

How baleful, then, if shady powers should lead

and gather those consumed with wrath and greed

into that struggle, darkening its advance

with flags of vengeance, hate, intolerance.

How hard for mankind to perceive the true

as a natural desire that can be realized.

How hard to know one’s way so early on.

How hard to stand there droning at the altar,

appealing to a god about whose laws

the only thing we know is that he suffers

from all that does not wholly serve his cause.

How hard to fit belief to daily living.

How hard to grasp a god of sacrifice.

How hard not to be thinking in our silence:

must still more sacrificial blood be let

and why have executioners not vanished yet?

How hard not to be thinking in our silence.

And practices of grace, how hard to grasp

for one who’s never spoken with the dead

and never found an answer from those graves

to which no fairies steal with magic staves,

for from death’s bonds only one has come

to meet his god when all the others, dumb

and blind among the miseries of decay,

must lie there till all time has passed away

How hard to keep one’s faith in life to come.

How right to have the wish for life to come.

It witnesses to a delight in living

and an urge to see its loveliness once more,

not simply die like dragonflies on shore.

How right to witness a delight in living.

How right to set one’s life above one’s death,

How hard the squirming in a grave-deep crevice.

How easv to believe in life to come.

Sunk in earth the generations lie

in stark-blind fields beneath the springtime wind

and as one choir they raise their voices high

in blindmen’s anthems to the land of Rind.

With the limbs of their bodies ravaged into soil

daily they celebrate their god gone blind

who knows all things and has no need to see

those shapes of life whose raiment he assigned.

The tender elements will rot away,

the solid elements are meant to hold;

but time does pass and soon there comes a day

when solid elements decay to mould.

And soon with ease their chorus is delivered

to the tops of trees, and every leaf is breathing

to any breeze that may be passing by

that death, lapped in summer, makes a joyful seething.

As selflessly as lovely summers do,

so the soul of life goes, as ungraspable

as lovely summers which have gone away

and every year come visiting anew.

Enthralled, we listen to the sightless maid.

Then several speak from where they stand, tight-lipped:

What lovely words she summoned to her aid.

What lovely words she came upon in Rind.

But merely words they are, and merely wind.

50 THE ARCH-COMIC SANDON

The arch-comic Sandon was living in space and delighted

each woman and man whom sensations of light-years united.

When the sun had averted its blaze from the bands of deported,

at our nightmare paresis the arch-comic Sandon cavorted.

If delight dropped to zero from suns glaring out from afar,

the arch-comic Sandon gave voice to a screech called a Blahr.

We howled when he entered on stage with his three-legged car.

Our thanks was a howl and he answered right back with a blahr.

But everything falls to the grave, which adores jeux d’esprit.

The arch-comic Sandon was lost in the vast cosmic sea.

Used up and worn down by the burdensome fortunes of man,

the arch-comic gave up his blahr, filling out his life-span.

51

A lady of the world, a beautiful gold leaf

upon a choice branch of the Yedis nobles,

exquisite of shape, her hair divided

on the left side blue, the right side black

and with a splendid stone comb

of rarest Yabian fire-agate

in a finely upswept bun, the height of hairstyle,

is describing to another Yedis lady

how, in her palanquin, she once looked out

from Geining Highland to the Setokaidi Sea,

where the moon rose like a perfect lantern

with the sated glow of autumn.

I find both of these ladies

on a day when I am sorting mima shards

and playing them in shock and solitude.

Once the mima captured their attractions,

the wonder of their beauty, Yedis-eyed.

And the language they had spoken at one time

the wonder of their beauty, Yedis-eyed.

And the language they had spoken at one time