Notes and comments for Martinson’s ‘Aniara’

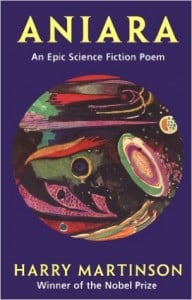

Cover of Aniara from Sjoberg’s translation

Overview of Martinson’s Aniara (1998) as a major GS text

Comments and descriptions for the poems

Links to the GS Project’s focus questions

Overview of Martinson’s Aniara (1998) as a major GS text

- Harry Martinson’s Aniara (1998) poetry cycle is not usually found in courses on Science Fiction (SF), though it is certainly named in commentaries on the subgenre of Generational Spaceships (GS) in SF. Martinson was a major Swedish poet and was made a Nobel laureate for his writings in 1974. He was self-taught and details of his early life and struggles against many hardships can be found in introductions to Aniara by translators Klass and Sjoberg (1998) as well as MacDiarmid and Schubert (1963). Aniara is well known in Sweden and was made into a two act opera by Blomdahl in 1960 with several contemporary musicians adapting his poetry to music, dance and performance. More can be seen on Blomdahl’s interpretation of Aniara here. While there have been several dramatic and musical adaptations of Aniara as well as a recent graphic novel (Larssons, 2016), there have been no films to date.

- Martinson’s Aniara (1998) has been influential in many SF texts including Tau Zero (Anderson, 1970) and Le Guin’s more recent long short story ‘Paradises Lost’ (2001) and links can be found in those texts and their discussions.

- First written in Swedish in 1956, it is said that Martinson was strongly influenced by many events contemporary with the writing of the first few poems in 1953 and then the full poetry cycle completed three years later. Martinson’s intimate observations of the natural world in his Scandanavian and other travels as well as his army experiences are seen clearly in his poetry but Aniara was formed by his observation through a telescope of the Andromeda Galaxy, his strong scientific interest in astronomy and astrophysics, as well as contemporary events. These events were the non-stop flight of a large airplane across the Atlantic, the Soviet testing of the Hydrogen bomb and the development of rocket science in Russia and the USA.

- Martinson is best known for his incorporation of science into his poetry and this was one reason for his Nobel Prize later in 1974. In Aniara, set in a human future where space flight between planets is commonplace due to a polluted and irradiated Earth and conflict everywhere humans have settled, the well-known device of SF techno-gabble is seen, with giant gyroscopes lifting the vast Aniara out of Earth’s gravity and the use of ‘phototurb’ fusion engines designed with ‘Gopta’ physics. Many realistic scientific terms are used and much of the technical language of travel in space is accurate, with Martinson changing words slightly for poetic effect. Additionally, Martinson does what many SF writers do and creates many new words, neologisms, as seen frequently in his poem cycle. In fact, he creates many more than most, enriching these new words, terms, places and processes with a love of the Swedish language and derivations in Latin and Greek, as well as his very strong understanding of the sciences, particularly in this poem cycle, physics, astronomy and even ancient Scandanavian mythic poems that have built contemporary cultures. Look up those places and names you do not recognise, you’ll see what Martinson has done, with clever borrowings from Hindi, Norse sage, Scandanavian folklore, principles of Euclidian geometry and astrophysics, all bent under his wry and canny will.

- Most importantly for many, there are several, major themes and narrative elements seen in this poem cycle Aniara (1998) that are very important and are built upon by other writers in the subgenre of GS and elsewhere. These include: (a) the opposition of the science/engineer crew silhouetted against the general travellers and those fanatics thrown up by them; (b) the rise (and fall) of cults or fantastical religions to make sense of the GS on its voyage; (c) the breakdown over time in the hierarchy of travellers, intermediary officers and executive of the craft, sometimes caused by ‘a’ or ‘b’, above; (d) the use of traditional myths, fables and legends as analogies to the GS travellers and their plights; (e) the descent to barbarism in a short space, even (or especially) for the society’s most sophisticated elites; (f) an occasional use of dry, sardonic humour that juxtaposes astonishing technological marvels with the most base conduct during a disaster; and of course; (g) the consensual surrender of cultural memory to break the link between past, present and future.

- It is the consensual surrender of cultural memory that is found in so many GS texts, often leading to anarchy, insanity, cannibalism and savagery, or for humorous effect.

Comments and descriptions for the poems

- Poem 1 sets the scene rapidly, firstly depicting the beautiful Doris who organises the refugees on the Aniara and what they should do. The narrator also tells the reader that Earth is given a necessary time of calm, repose and, most importantly quarantine because it is unclean with toxic radiation. Doris is blond and she has gleaming nails. She gives brisk instructions to the refugees and tells them they can choose the part of the Martian tundra they prefer and also assures them of their one jar of uncontaminated soil. Doris looks at the narrator with disdain. In this way Poem 1 tells us the Earth is contaminated and unfit for habitation and that many refugees are travelling, to what seem to be unappealing sections of tundra to work and all they have to work with is a jar of clean soil.

- Poem 2 describes the way the spaceship, called a Goldonder because of its origin and Aniara as its name, is lifted by extraordinary technologies out of the gravity well of Earth. This is a perfectly normal ascent clearly set in a far distant future where technologies can lift vast spaceships through gyroscopic and magnetic forces. The last part of Poem 2 foreshadows the terrible fate of the Aniara in the narrator’s voice as he counts himself as a traveller who, like all the others, is severed “from Sun and Earth, / from Mars and Venus and from Dorisvale.” (Poem 2)

- Poem 3 swerves to avoid an unknown asteroid, named the ‘Hando’ and they are pushed off course. There are “swarms of leonids” (Poem 3) or asteroid showers and the Aniara heads towards two known asteroids but by the time they reach the Field of Sari 16 they could not turn around and instead they head through the empty centre of a ring of rocks but they were hit hard by rocks and pebbles. The Aniara and its travellers are aimed at the Constellation Lyra, called Lyre in the poem cycle. No change in course is possible but the gravity system, heating and lighting remained intact. The narrator ends Poem 3 with the note that, “Our ill-fate now is irretrievable. / But the Mima will hold (we hope) until the end” (Poem 3). This special attention to Martinson’s invention of a partly sentient technology, the Mima, is given special attention because the narrator is the officer on the Aniara who controls the Mima, in part. His role and title is the Mimarobe and he carries no other name.

- Poem 4 closes this section on the disaster that leaves the Aniara plunging towards Lyre without control or remedy. The short description of the disaster is completed with the wry note, “That was how the solar system closed / its vaulted gateway of the purest crystal / and severed spaceship Aniara’s company / from all the bonds and pledges of the sun.” (Poem 4) The call sign of Aniara is lost until, with distance, it simply fades away from any possibility of help.

- Poem 5 introduces the female pilot of Aniara, a key character in the poem cycle. The narrator, the Mimarobe, knows her because she comes to watch the Mima frequently. There are several pilots for the vast ship of eight thousand travellers and they act nonchalant after the tragedy but the narrator skips straight forward in Poem 5 to five years after the collision. The pilots seem nonchalant but “grief can shimmer like a phosphorescence / from their observer-eyes” (Poem 5)

- The Mima is a machine with advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) and even its creator only dimly understood it. In a special Mima Hall, tended by the narrator Mimarobe, it shows traces of pictures, landscapes and scraps of language but where these come from, no-one can tell. The narrator tends the Mima (Poem 6) and knows it is worshipped, “a sect of Mima-worshippers bows down, / fondling the Mima’s pedestal and praying / the noble Mima’s counsel for the journey, which now has entered on its sixth long year”. There is comfort in the Mima, as it gains “the power to soothe all souls / and settle them to quiet and composure / before the final hour that man must always / meet at last, wherever it be lodged” (Poem 6).

- The travellers keep the rituals of day and night and even celebrate Midsummer night, “/ Thev’re dancing there until the sun comes up / in Dorisvale. Then smack comes clarity, / the horror that it never did come up, / that life, a dream before in Doric vales, / is even more a dream in Mima’s halls.” (Poem 7)

- The passengers live in fantasy and it is only during a funeral that they think of the Aniara itself, “then come a multitude of black thoughts flapping / through these vaults that hold us bound” (Poem 8) and they rush to the Mima to be comforted by the images and snatches of life elsewhere.

- There are eight thousand on board, with Aniara’s length of 4.8km and 914 metres at its widest. The Ariana is one ship amongst thousands but now they are off course and they are a pioneering voyage and a probe.

- In Poem 9 Martinson uses the same sort of Science Fiction techno-babble as seen when describing Aniara’s launch and collision with meteorites in Poems 3 and 4. In this poem the Mima is adjusted for the “third webe’s action / in the focus-works / and the ninth protator’s kinematic read-out / in the flicker phase before the screener-cell” (Poem 9). The Mima was so advanced that half was invented by the Mima ‘herself’. The Mima comes to understand herself, “a telegrator without pride, industrious, upright, / a patient seeker, lucid and plain-dealing, / a filter of truth, with no stains of her own”. Amidst the despair, there is hope from the Mima, “the grace this Mima is conferring / is glimpses of the light of perfect grace / that seeks us in the barren house of space” (Poem 9).

- Then there is the repeated, powerful vision of the vast space about them, “The sterile void of space is terrifying. / Glass-like is the stare encircling us / and the systems of stars hang frozen and still / in the round crystal windows of our ship.” (Poem 10). There is “a massive, radiant hall of utter distance” but words can not cope with space.

- One from Aniara’s High Command says there have been worse disasters, as when a goldonder with fourteen thousand souls plunged into Jupiter. He says “But we are favored people. We’ve not crashed / on any star or stellar satellite. / Instead we have our trek ahead of us, / a lifelong journey onward to an end / which would have come in any case, and comes.” (Poem 11).

- The passenger fill their time with amusements. Our narrator dances the yurg with Daisy Doody from Dorisburg. The poem switches from the narrator, the Mimarobe to another mind, to Daisy, and in her voice the reader hears the slang of Dorisburg, her home city “/ I’m no sleeping chadwick, Daisy pouts, / my pipes are working, I am flamm and gondel, / my date’s a gander and my fate’s a rondel / and wathed in taris, gland in delt and yondel” (Poem 12).

- The wonderful metaphor of the bubble in glass to describe Aniara’s movement through space towards the Constellation Lyra is seen at Poem 13, “In any glass / that stands untouched for a sufficient time, / gradually a bubble in the glass will move / infinitely slowly to a different point / in the glazen form, and in a thousand years / the bubble’s made a voyage in its glass. /

- Similarly, in a boundless space / a gulf the depth of light-years throws its arch / round bubble Aniara on her march. / For though the rate she travels at is great / and much more rapid than the swiftest planet, / her speed as measured by the scale of space / exactly corresponds to that we know / the bubble makes inside this bowl of glass.” (Poem 13). The narrator runs from this image and takes solace in Daisy’s arms.

- A sect grows up, called the Ticklers, at Poem 14. The narrator tells the reader their sect worships fire and he tells the story of fire from his childhood and remarks that the fire was a piece of wood but wood became rare and even extinct, due to nuclear catastrophe. The narrator hears the story of a kind spirit, Nobby, who was herself radiation-blasted but helps others, collecting for charities to help those on Mars and Venus. At Poem 15 we hear the voice of the old space mariner talking of Nobby. We learn that prison ships take political prisoners to work in the tundra fields and the political situation was so changeable that one day you could be a citizen and the next a prisoner. The poems can enter the voices and minds of others but then comes back to the narrator who tends the Mima, the Mimarobe.

- The narrator tells the reader of the female pilot who wounds with her beauty but seems unapproachable. She sits to watch the Mima and, “The fair one’s white cheeks brighten instantly / and hotly blush: she fills with heavenly transport / when the Mima shows her everything there is / of pleasure inaccessible in worlds of space.” (Poem 19). The Mima starts to show a world too like the one Aniara left and the narrator turns off the machine. The female pilot thanks him and leaves but he thinks of Doris and wonders where she is, missing her comfort.

- The narrator uses the Mima to console the travellers but she shows only truth so he must control what is seen in case it hurts the audience, rather than comforts them in their loneliness and despair, “And on our ship, whenever anxiety patters / and dread and unease play havoc with our nerves / I serve up helpings of the Mima’s dream-preserves.” (Poem 21)

- In the sixth year of the voyage some are losing their sanity, even the senior astrolobe (Poem 23)

- At Poem 26 the narrator (or poet?) has one of the dead tell of a nuclear explosion in Dorisburg, the home of Daisy, and the terrible end of that beautiful city, state or memory. The narrator describes the explosion as a phototurb that explodes the dead man’s eardrums as he tells the story. Another of the dead describes the end of his world in nightmarish fashion, “He mentioned only one detail: he saw by neck. / His entire skull became an eye / blinded by a brightness beyond flashpoint / lifted and sped off in blind reliance / on the sleep of death. But no sleep came.” (Poem 26)

- The Mima shows the destruction of the beautiful planet or city and its truth is seen by all. As the Mima’s operator he is shocked by the display and its reception by the Aniara travellers.

- At Poem 28 it is clear that the destruction of Dorisvale affected the half-sentient Mima profoundly and she talks with the narrator, telling him that she felt the destruction of the planet in nuclear war. The travellers flood into the hall to watch the Mima display but she has had enough of man’s sin (Poem 29) and she dies, creating a character called the Detonee to explain the sensation of disintegration (Poem 29).

- The narrator cannot fix the Mima, who has suicided, so the travellers are deeply unhappy that their entertainment has ended. One of the travellers, Chefone, rises as a chief or a demagogue within the unhappy mob and he attacks the narrator, saying he will be tried and punished. The narrator cares little for Chefone but Chefone’s power grows.

- Chefone orders persecutions of the scientists and the narrator and his power helps the most worthless of the travellers to rise, criticising science itself, “In endless muddle people sought to prove / the Mima’s tragedy was our misdeed, / for all our egos had defiled her screen” (Poem 31)

- The scientific elite try to defend themselves but they do not seem to be able to communicate with Chefone and his supporters. After three years from the death of the Mima the narrator is taken up again into normal Aniara society (Poem 32) and he has also nearly lost his own sanity. He is expected to start the Mima again.

- The female pilot, Isgael, has been confined with the narrator and she has confided in him. They have grown closer, “And our eyes meet and lock, and soul to soul / we stand, unspeaking. Isagel I love heartwhole.” (Poem 34)

- The narrator Mimarobe finds the Aniara society has been taken up with cultish worship, with an active priesthood and strange rites. Because he was responsible for the Mima he is given roles in their rites. (Poem 35)

- He cannot repair the Mima but instead has mirrors put up to every side of the Mima hall where the rituals are held and the travellers revel and dance, reflected endlessly in the octupled mirrors (Poem 36) The narrator even fools himself into a mad dream and dances with the female ritual leaders. The female pilot, Isagel, also has a part in the strange rituals, blessing the Mima’s broken shell three times.

- Libidel is a female priest of the cult and as the years pass by with Aniara caught like a bubble in glass, she worries that her advancing age will mean she has to leave her high position in the cult. In Poem 38 it is as if all the travellers have forgotten their plight and are wasting their years away in superstition and ritual, including the narrator and the scientific crew.

- In Poem 39 Isagel is found again, working on the famous mathematical problem of Jender curves. The narrator likens her breakthrough to the birth of an infant. Unfortunately, the breakthrough is linked to join the Aniara “going out / ever farther to the Lyre and then to vanish” (Poem 39). Nevertheless, the narrator and Isagel share a joy in pure ideas.

- In Poem 40 the voice changes again to ‘The Space-Hands Tale’ who speaks of the packed transport ships and the terrible treatment of the immigrants to their new homes. The kind and generous Nobby appears again in the sparse and frigid cold of Mars and while her surrounds are desolate she found beauty in that harshness. The Space Hand remembers the time with Nobby as the “last spring nature was alive” as the nuclear war hit Xinombra and survivors became wild gangs of convicts who killed the less aggressive, as. “The unresisting souls on all our lands / died complaisantly of those rough bands” (Poem 40) The Space Hands ends with a note that if it were not for his story no-one would know of Nobby’s deeds and character.

- Poem 41 is a sad poem based around a character met earlier, Chebeba, who was an enthusiastic dancer of the rituals. Her infant is dead and laid on a bier and Yaal, another performer of the rituals, says the infant is going home and that their prison is ‘Aniara-town’. Women come in and look at the infant lying on the bier with different reactions and Heba’s response, the last of the performers of the rituals, is only to look upon the infant, “asleep, afloat into the day of days / from Aniara-town” (Poem 41).

- Like Poem 41, Poem 42 returns to an earlier character and in this we enter into the mind of Libidel. Her voice is distracted, alone and frightened, quite unlike the Libidel we hear about earlier in Aniara. Like other poems, there is a reference to the colour blue and Libidel believes the ‘staring cold outside’ Aniara can be fought through human contact and sex and she invites in the reader for some ‘warmth’.

- At Poem 43 the voice changes again, leaving the thin and frail Libidel who used to be so admired and sought after. Now, the Aniara poem cycle moves to a consideration of how the travellers used to crowd around the Mima and how the controller (the narrator himself) used to change the channels when the viewing became too difficult and realistic and painful.

- The narrator understands that even though they sought nicer visions than death and war from the Mima, they still loved to watch the battles and witness the butcheries, “We would look upon the felled / lying prone and still, but then rushed past / to be in on it when the next wave swelled” (Poem 43).

- The Mima showed it all and, after a while, those who watched called the worst atrocities and butcheries the Peaks and the lesser evils were put out of mind. Poem 44 is another view of the travellers on Aniara who have access to extraordinary stores of cultural knowledge. Even though Chamber Seven of the ship has repositories of important information on how the travellers could avoid their mad rituals and despair, regardless of this some would request instead odd details that would become “a new twist” that would briefly snag / new interest” until that, too, would flag.

- Running all the time on Aniara the Calculator is available to point out the truth of this ship in its bubble of glass/void. This simple device points out that there is no hope for the travellers, and as a consequence, is ignored.

- Poem 46 is important and often quoted in discussions of Martinson’s Aniara. Like other poems, this seems to relate directly to experience in contemporary society, talking of a system that plays music or voice through a ring worn on the left hand. These can be exchanged with others to enjoy a wide variety of entertainment. Here in this poem the focus contracts to Heba, who is listening to a performance of someone else’s player but flinches when she hears “calls for help and pleas for mercy” coming from the devastated world of Gond. (Poem 46) Again, the poet brings us back to the despair of the travellers but also the disaster of humanity itself in this future where it annihilates itself on distant planets.

- Poem 47 turns back to the mathematician and astrogator Isagel who is bought new data from those trying to find a way out of the Aniara’s loss in the great void. Isagel is polite and receives the data, looking for a miracle, but the head mathematician, called ‘Dr Quantity’ by the narrator, “makes a silent bow, resigned to grief, / and tiptoes down Aniara’s passageways” (Poem 47) There is no hope for miracles for this crew and the travellers.

- Poem 48 introduces the blind poet of Rind who makes the narrator happier with her myths and fables that are lovely, though they are composed in the dark, returning to the theme of darkness and void that enshrouds the Aniara. Poem 49 continues with the blind poet in her voice and in a new scheme of poetic expression. The poet describes the beautiful, cold darkness of Rind that would be changed by the approach of summer. However, the poet has a presentiment that even nature knows there will soon be a summer lying dead in ruin. She feels the nuclear disaster coming and in the night comes the terrifying heat of the blast. She is sheltered by someone who wants to protect her eyes from the blast glare but explains she is already blind. He runs away and the poet creeps away through thunderclaps of explosions. She is saved, but not for anything but the forced labor camps of the Martian tundra. There is a plan to regrow the vegetation of Rind with a new substance ‘geosan’ and the poet leaves on another spaceship to become an official singer, singing sentimental and patriotic songs in Chamber Three. The blind poet says how hard it is to keep her faith in God amidst the suffering but how sensible it is to believe in a future world where life is better. Her poetry is beautiful and those gathered around listen carefully but others note with wry irony, “What lovely words she came upon in Rind. / But merely words they are, and merely wind. ” (Poem 49)

- Poem 50 is a change in pace and speaks of a comic player called Sandon who had a trademark speech or screech called Blahr and he causes great laughter but even this is lost in the vast cosmic sea of Aniara’s journey and Sandon dies, giving up his blahr and “filling out his life-span.” (Poem 50)

- Poem 51 looks at a beautiful noble woman from Yedis who was used to great finery and admiration and she describes her elegant past to another lady when the narrator finds them whilst sorting shards of the broken Mima. He notes that “Nothing now makes sense” and this introduces Poem 52 ‘Shards from Minia’ that contemplates a sarcophagus from four million years before, probably found amongst the Mima shards of memory, of a fine woman in her beautiful garments from a city, place and world now destroyed.

- The narrator questions the reader about the omnipotence of god and human frailty but he ends with irony to say the fashions of four million years before can now be adapted to the latest fashions from the much more recently devastated Dorisburg, helping the reader remember his dancing lover, Daisy, who danced and sang even as her world disintegrated.

- Poem 53 ‘The Spear’ chronicles a view of another traveller in space, some sort of meteorite or debris, that comes from the same direction but sped ahead and disappeared. The travellers discuss it but it all of no help and, “Three went mad, one was a suicide. / And still another started up a sect,

- a shrill, dry, tediously ascetic crew” (Poem 53). This talk of the sect brings the reader back to the leader of the cult from many years before, Chefone.

- Poem 54 is ‘Chefone’s Garden’ which is a sort of greenhouse on a spaceship like Aniara that are minature paradises of “soft living greenery” (Poem 54) Chefone asks the scientists how to protect his greenhouse, called ‘Spring Evermore’ and they look about and see a beautiful parkland. The scientists., including the narrator, drink and when they see a naked woman the narrator draws close and asks her how she came to be there but she answers with hate, because as a scientist he is one of those who destroyed all life in Xinombra at the time of the nuclear war.

- The narrator walks away, ashamed, and thinks of ancient poems of dragons and their lairs and the poor women they kept there in fable and he imagines that he is a pair with the dragon, though it is the old and cruel boss Chefone that keeps her in the ‘Spring Evermore’ greenhouse.

- Poem 55 speaks of the Planetarium deck of Aniara that has a plexi-dish through which can be seen the distant galaxies. The astronomer on board Aniara describes the flaring of a nova with its own nuclear furnace, like the photoflares that destroyed the home worlds but a traveller mocks him and the astronomer freezes and ends his talk. Again, we see the hatred of technology and science, especially amongst those who followed the mindless rituals of the sect.

- In Poem 56 the narrator meets Chefone again but years have passed since he was imprisoned by Chefone’s gang. Chefone mocks the narrator but then leaves “bored senseless by all tears” (Poem 56), showing a change in his character that leaves the narrator wondering where sanity lies on Aniara.

- Poem 57 tells of the suicide of fair Libidel and singing by her grave before her body was cremated and the narrator notes that for her and many, “love had rusted” (Poem 57).

- In Poem 58 a rival cult to Chefone’s arises, this cult dedicated to fire and light as seen earlier in Aniara’s flight and this worship of light chooses the blind poet of Rind. Her poem is eloquent and strong, repeated descriptions of the end of Rind where her means of sight was her perception of nuclear heat and flare on her skin. The narrator says that he attends the sect’s meetings several times as, “on me it left its mark / and on many others in this sea of dark” (Poem 58).

- Poem 59 speaks of another part of Aniara called the Memory Hall where the Mima’s performances were so well attanded but now there are groups who torture themselves and confess their own guilt for the endless journey into blackness onboard Aniara.

- The narrator loves to listen to the Astronomer talking and is reminded that the situation of Aniara falling through the void is just a tiny moment in geological and planetary history. The Astronomer reminds his listeners of other times past when thousand year empires rose and fell into sand, when ice ages came and went and when the sun passed too close to one civilisation and annihilated it.

- In Poem 61 the narrator describes how he finally gathers together the shards of the Mima and projects images of woodlands and moonlit lakes against a screen as a sort of never-ending slideshow of natural beauty. The screen shuts off the reality of the intolerable space outside Aniara. He rigs another screen to block out the view of Aniara’s forward motion through the abyss. But this is not enough. The narrator is given death threats by those who cannot be diverted by the screens and who are still oppressed by the blankness of the surrounding space. The narrator says that the blankness comes from within the viewer and cannot be replaced by the magic arts of the screens and their projections.

- In Poem 62 the narrator describes the new physics developed by Isagel and others to explain space mechanics and movement but within himself, he hears the endless fight between light and void in every star but he does not communicate this. Instead, at the end of the lecture, he sees the cadets he was lecturing leave for another, equally pointless lecture on how to build a spaceship.

- While many on Aniara grow ‘space-cold’ there is a couple who came every day to the vista room, carrying their luggage. They were ready for disembarking and gazed with confidence towards ‘Lyreland’ a fanciful name for the Constellation Lyra towards which the Aniara was heading.

- They remind the narrator of a planetbound life, of the smell of herbs and the making of bread in the oven “they had left back in the land of Gond” (Poem 63) They sit and read and wait and the narrator watches them turn grey and then the husband died and the narrator observes the exile sitting “lonesome, mute and bent” while the rest of the travellers grow more despairing of the ‘Promised Land’.

- Poem 64 introduces a new voice from the dead of Xinombra and this is a fine poem chronicling the creeping death after the nuclear war on Rind when, “Religions were tangled on the lines of thought

- in gulfstreams of death” (Poem 64).

- Poem 65 is an halucination or a vision of the future when there is no Aniara, when the cult chief Chefone was dead and the terrible world of the travellers is resolved in endless quiet and stillness.

- The quiet is broken in Poem 67 by Chebeba’s scream of sudden, complete nuclear destruction in her memory and the narrator tells us the speed and ferocity was like, ” an alarm clock on a nightstand / set to measure out the time in seconds / is caught off-guard by its own liquefaction / and then boils up and whirls away as gas / and all this in a millionth of a second” (Poem 67).

- There is a sudden movement of Aniara in Poem 68 and many hope it is their destruction, especially the old who are wearied of psychological pain. Aniara begins to toss in her flight. In response the different religions, the new cults and all the different groups of the remaining travellers gather in the halls and “hope was unbalanced by terror” (Poem 68).

- In Poem 69 the narrator tells us the ship has entered an area of particle showers that has strange impacts on Aniara. The travellers think they are “foundering and dying” and there are many deaths and injuries when the gravitional thrust is dislocated by this cosmic sand cloud which, “blazing, blinding, burst into extinction / against the shocked metals of the fuselage” (Poem 69) but then the storm is over as suddenly as it started and Aniara dives “along the loxodrome / to which in her fall she clove” (Poem 69) where a loxdrome is an arc that intersects all meridians of longitude at the same angle. This use of geometric language heightens both the sense of scientific veracity of the poem and its rich and colourful language, requiring some consultation with a definition.

- The travellers ask what the particle could have been and what it meant and the High Command pronounces the disturbance the effect of cosmic granules or of ice that has settled on Aniara. The travellers are pleased by the explanation and take away the dead. The disturbance has shattered the hall of mirrors and cut to pieces the performers, including Heba, Daisy, Yall and Chebeba is badly hurt. The narrator does not comment on Daisy’s death and the poem seems to indicate this great change was a major change for Aniara in her flight. This is on the twelfth year of travel.

- Poem 70 places Aniara in the Ghazilnut, a small part of a vast galaxy and the narrator adds that words are not enough to measure the distance of “Aniara swallowed up in the abyss” (Poem 70)

- Poem 71 takes the reader back to the Space Hand with his story of Nobby and his thoughts wander back to a rough town called Tlaloctitli and the Space Hand gives the amount in the currencies of several planets needed to build the place.

- Poem 71 is ‘The Song of the Karelia’ is the narrator’s memory of a land he knew before joining the Aniara crew. Karelia is a place that borders Finland, Sweden and Russia but in the poem it is a visionary place like a silvery lake seen through branches. The narrator slips between images and memory and recalls a folk tale of murder from Karelia of the fallows.

- Poem 73 is the Libidella ‘Secret Dirge’ is a nonsense rhyme even in translation asking questions of the audience then moving into a garbled rhythmical language, with a hint of erotic fantasy, “O nuda you / pitch nudie woo / in a moonwood of lutes for two” (Poem 73) It sounds like an ancient fertility song best sung with a belly of mead.

- Poem 74 moves from this nonsense verse to a stark clarity of the plight of the Aniara and its travellers, reminding themselves and the reader that the light of horror blazes in the abyss.

- Absurdly, a prize is offered for anyone who can rotate Aniara so that she faces back towards Doriswold. The narrator reminds us of dead Daisy in her tomb in the hold and asks, “Who’ll give the fairy back her fairy-wand? / That is our cry in the oceans of beyond.” (Poem 75)

- The space historian lectures in his own voice in Poem 76, telling of the different ages of space conquest and how in all of these there were many casualties. Comparing that with Aniara’s fate it shows the brutality of their own age of space.

- Poem 77 talks of black burial grounds in space, the darkness between stars and galaxies that are like graves piled with dark Earth, these Black Holes that reflect no light and “hemmed in by the coal-black slag, is frozen / nameless in light’s grave and without trace” (Poem 77) is a strong and evocative description in poetic form.

- Poem 78 looks to the Chief Engineer, another memorable character on board the doomed Aniara, who died recently and wished to have his body shot out in a rescue-module towards Rigel. Many of the travellers witnessed the event that the narrator describes as, “The death-capsule was channeled through / to its light-year grave” (Poem 78)

- The voices change more rapidly in this part of the Aniara poetry cycle and Poem 79 is a look back at all the travellers from a bright and fertile planet and the narrator says “God and Satan hand in hand” fled in these deranged and poisoned lands from man, “a king in an ashen crown” (Poem 79).

- Poem 80 changes tone again and describes the gentle fertility of the home planet that was sustained by the same furnace sun that now can be seen plainly from Aniara. Just as nature is nurtured by sunlight, humans should have understood the lesson to be good and not bring down the sun of nuclear war on the land.

- Poem 81 charts the rise of the dark in the minds of the Aniara travellers after nineteen years, although the narrator now works on scientific theories with Isagel, who is his companion as the ship drove on “with its hull full of scars” (Poem 81).

- The High Command of Aniara has the whole crew and all the travellers dress up in their best for a ritual to celebrate the Cosmic Way, like a shipload of passengers crossing the equator on Earth. When the survivors were together for the event they notices how hard the years had been on them. The Chief Goldondier gave a speech to mark the occasion of the twentieth year of travel and then the narrator notes that, “suddenly someone said / a light-year is a grave” (Poem 81), meaning that just one light year is too great a distance for a human being. The narrator says the twenty years of the journey were, “sixteen hours of a light-path / on the sea of the light-year grave. /Then none of us were laughing” (Poem 82) The poem ends with the forceful line, “A light-year is a grave.” (Poem 82)

- ‘The Song of Erosion’ is Poem 83, very similar to Shelley’s ‘Ozymandius’ (1818) that mocks the pride of the priests, kings and rulers for their lavish statues and rituals that are all reduced to dust. This fine poem in the Aniara cycle brings back the memories of the strange rituals of the cults onboard Aniara and how the twenty year voyage has eroded their strength and meaning entirely.

- Poem 84 returns to the Chief Astronomer who is lecturing the Aniara travellers and shows an image of as distant galaxy and the narrator tells us some of the listeners pray to the image on their knees as they are members of the “galactave religion” (Poem 84) and the narrator stressed the visual impact of the image by saying it is like seeing a goldfish magnified in a bowl.

- As in earlier poems, Poem 85 starts by declaring that words are not equal to the task of describing space with the fine example, “The galaxy swings around / like a wheel of lighted smoke, / and the smoke is made of stars. / It is sunsmoke. / For lack of other words we call it sunsmoke, / do you see. ” (Poem 85) The richest of all languages cannot describe the immensity of the universe.

- Poem 86 is the ‘Song from Gond’ and it seems to be placed in the cycle by the narrator as it relates directly to the ageing travellers on the Aniara, the transience of human life in comparison to the universe, and in this poem’s case to the gods. This is a shorter poem in rhyme and meter, keeping in translation and form from Martinson’s original.

- Following on from the appreciation of the short cycle of human birth and death comes Poem 87 that depicts again in the narrator’s voice how the static world of Aniara causes the travellers to move through stages, through fleeting fashions and strange superstitions. When a star draws nearer Isagel asks the narrator if they should plunge Aniara into the sun but the narrator says to wait, showing this couple’s deep depression.

- Poem 88 carries on from the glimpse of despair seen in Poem 87 with Isagel’s madness. She hears the Mima speak to her and call her by name and her fine, Mathematical mind now craves death. The narrator says she “slipped away to where / the Laws of Aleph Numbers all are stored” (Poem 89) He notes, “When someone you have loved has reached death’s door / space stands harder and more brutal than before.” (Poem 89)

- Poem 90 tells of how during Aniara’s long voyage the narrator is taken by some of Chefone’s gang and locked in a low cellar room. He believes he will be released when someone is needed for the ship with scientific skills and his prediction comes true rapidly. The narrator speaks to his dead partner, Isagel, from his confinement and now believes Isagel was the Mima’s soul. Chefone releases the narrator and he returns to Mima’s hall, perhaps to be closer to Isagel.

- In Poem 91 it is clear the problem with Aniara is the artificial gravity and its malfunction means the travellers feel as if they are continually falling. The narrator uses his scientific skills and the normal gravity is restored.

- Poem 92 returns to the Mima again and its meaning in the lives of the Aniara travellers, perhaps because the narrator is living back with the broken relic of the Mima. He sees that there are some travellers who still worship the broken Mima and their cult is so extreme that they even practise human sacrifice. Even these killings seem lukewarm to the narrator and others, who remember the visuals of the end of their homeworlds in nuclear holocaust. They are so jaded and emotionless that they refuse to perform one of the rituals Chefone designed, that “thrasonical / bullet-headed breaker of mankind” (Poem 92).

- Chefone’s response to their slight was to have the priests of the religion killed brutally in the Mima halls where the rituals were performed. This makes the Aniara travellers stay away from the halls and even Chefone realises his time is over. At the end of Poem 93 the narrator is himself surprised that Chefone changes his ways and helps the sick “and tried to warm the freezing” (Poem 93)

- The title of Poem 94 is ‘Death Certificate’ and with this poem the narrator announces Chefone’s demise and lambasts him as an “ill-willed hateful self-devourer” and a ” froth-mouthed feeder” (Poem 94).

- In Poem 95 the narrator slows the pace of the poems and brings in the element of the slow and quiet death of the Aniara travellers. This is continued in Poem 96 even though the High Command try to keep the inevitable death of all onboard concealed.

- The narrator states that in the twenty-fourth year of Aniara’s journey “thought broke down and fantasy died out” (Poem 97). The travellers roam the halls and speak of days long past and they cluster around the lamps “as moths abound / in autumn over distant Doric ground” (Poem 97)

- There is a sudden change in voice in Poem 98 as the narrator calls on the spirit of his beloved Isagel to rise from the Mima’s hall and assist him in his own death.

- He returns to his own voice in Poem 99 and says the time is very late and that Aniara is now a sarcophagus. The pilot’s cabin was empty and most of the travellers were laid out in the dance hall where Daisy Doody slept. The ship is hushed but the narrator walks many steps to the Mima’s halls where some sit shivering in the dark and cold. One of them is mad and raves about human exploration and how much humankind had discovered but most of his audience is dead and the Aniara has gone further than any other human exploration.

- The narrator tells the reader there are no longer any lights to light in Poem 100 but one light still burnt at the Mima’s grave. A few survivors sit near this light and the narrator says this is like humans waiting for execution on Earth with the last light of their lamps while the firing squad prepared. He makes a judgement on human nature, saying, “the fierceness of space does not exceed mankind’s.

- No, human cruelty stands up more than well. / In the desolation of a death-camp cell

- space made of stone enclosed the souls of men, / and the silence of the cold stones met the ear:

- Here mankind rules. Aniara’s ship is here. ” (Poem 100)

- Poems 101 and 102 are short, of two stanzas and three. The narrator says that as they approach death the individual’s sense of self broke down and disappeared but their soul’s will or essence became clearer. In a strong confession the narrator says he tried to make people happy through the Mima and, in the end, there is compassion and love, even though the four thousand travellers are killed by the scientific fact and ultimate truth of their journey through seemingly endless void.

- In Poem 103 the narrator turns down the last, remaining lamp and waits for peace. Predicting the future of the Aniara he says the spacecraft travelled on for fifteen thousand years to Constellation Lyra, “like a museum filled with things and bones / and desiccated plants from Dorisgrove” (Poem 103) There is a glass-clear silence in the cosmic night as their sarcophagus ship travels on. He ends with a clear image of the dead around the Mima’s grave, “sprawled in rings, / fallen and to guiltless ashes changed, / delivered from the stars’ embittered stings” but he adds a line of hope and transcendence for although they are all dead and turned to dust in the vast and empty ship, them all of their human souls a constant current ranged of Nirvana, a state of release from mortal bonds and cares, a state of perfect freedom.

Links to the GS Project questions

The focus questions for the GS Project texts presented are –

- What is worth holding onto over the generations?

- What should be discarded for the voyage? and

- Can life be sustained in the GS …or on Earth?

Only a few comments are made here related to the three questions, above, mostly because the narrative itself will be interpreted differently by different readers. But what might be noted are the following:

- Much is lost amongst the eight thousand travellers on the Aniara. What does the narrator (the Mimarobe) tell us should be retained?

- What are the social and individual characteristics that the narrator and author feel should be discarded on the Aniara? Who represents the worst of the society of Aniara?

- The poem cycle Aniara (1998) does not examine the sustainability of spaceship Aniara but it is clear that there is no real problem with power from the engines, nor heat and light. Food is replenished by onboard ecosystems. Why is the Aniara doomed as a GS? What stops the travellers from continuing to Constellation Lyra, through their children? If the Aniara is like Earth, are doomed also?

Resource List

Blomdahl, K-B. (Composer). (1962). Aniara – An Epic Of Space Flight In 2038 A.D. USA: Columbia Masterworks. M2L 405 .

Klass, S. & Sjoberg, L. (1998) Introduction. In Aniara: An Epic Science Fiction Poem. Translated from the Swedish by Klass, S. & Sjoberg, L. USA: Story Line Press.

MacDiarmid, H. & Schubert, E.H. (1963) Introduction. In Aniara: A review of Man in Time and Space. Adapted from the Swedish by MacDiarmid, H. & Schubert, E.H. English edition. New York: Avon Books.

Martinson, H. (1963) Aniara: A review of Man in Time and Space. Adapted from the Swedish by MacDiarmid, H. & Schubert, E.H. English edition. New York: Avon Books.

Martinson, H. (1998) Aniara: An Epic Science Fiction Poem. Translated from the Swedish by Klass, S. & Sjoberg, L. USA: Story Line Press.

Ott, A. (1998). Aniara: On a Space Epic and its Author. In Planetarian, Vol 27, #2, June 1998.Accessed 22 January 2016 from http://www.ips-planetarium.org/?page=a_ottandbroman1988

Back to the index