‘Taklamakan [Chattanooga]’ by Bruce Sterling

Sterling, B. (1998) Taklamakan [Chattanooga]. In Asimov’s Science Fiction. Vol.22, No.274, October/November, 1998. Accessed 6 February 2016 from http://lib.ru/STERLINGB/taklamakan.txt

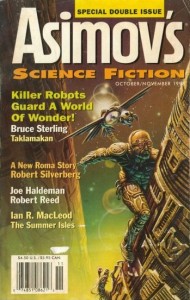

Cover of Asimov Science Fiction October 1998

A bone-dry frozen wind tore at the earth outside, its lethal howling cut to a muffled moan. Katrinko and Spider Pete were camped deep in a crevice in the rock, wrapped in furry darkness. Pete could hear Katrinko breathing, with a light rattle of chattering teeth. The neuter’s yeasty armpits smelled like nutmeg.

Spider Pete strapped his shaven head into his spex. Outside their puffy nest, the sticky eyes of a dozen gelcams splayed across the rock, a sky-eating web of perception. Pete touched a stud on his spex, pulled down a glowing menu, and adjusted his visual take on the outside world.

Flying powder tumbled through the yardangs like an evil fog. The crescent moon and a billion desert stars, glowing like pixelated bruises, wheeled above the eerie wind-sculpted landscape of the Taklamakan. With the exceptions of Antarctica, or maybe the deep Sahara–locales Pete had never been paid to visit–this central Asian desert was the loneliest, most desolate place on Earth.

Pete adjusted parameters, etching the landscape with a busy array of false colors. He recorded an artful series of panorama shots, and tagged a global positioning fix onto the captured stack. Then he signed the footage with a cryptographic time-stamp from a passing NAFTA spy-sat.1/15/2052 05:24:01. Pete saved the stack onto a gelbrain. This gelbrain was a walnut-sized lump of neural biotech, carefully grown to mimic the razor-sharp visual cortex of an American bald eagle. It was the best, most expensive piece of photographic hardware that Pete had ever owned. Pete kept the thing tucked in his crotch.

Pete took a deep and intimate pleasure in working with the latest federally subsidized spy gear. It was quite the privilege for Spider Pete, the kind of privilege that he might well die for. There was no tactical use in yet another spy-shot of the chill and empty Taklamakan. But the tagged picture would prove that Katrinko and Pete had been here at the appointed rendezvous. Right here, right now. Waiting for the man. And the man was overdue.

During their brief professional acquaintance, Spider Pete had met the Lieutenant Colonel in a number of deeply unlikely locales. A parking garage in Pentagon City. An outdoor seafood restaurant in Cabo San Lucas. On the ferry to Staten Island. Pete had never known his patron to miss a rendezvous by so much as a microsecond. The sky went dirty white. A sizzle, a sparkle, a zenith full of stink. A screaming-streaking-tumbling. A nasty thunderclap. The ground shook hard.

“Dang,” Pete said.

They found the Lieutenant Colonel just before eight in the morning. Pieces of his landing pod were violently scattered across half a kilometer. Katrinko and Pete skulked expertly through a dirty yellow jumble of wind-grooved boulders. Their camou gear switched coloration moment by moment, to match the landscape and the incidental light. Pete pried the mask from his face, inhaled the thin, pitiless, metallic air, and spoke aloud.

“That’s our boy all right. Never missed a date.”

The neuter removed her mask and fastidiously smeared her lips and gums with silicone anti-evaporant. Her voice fluted eerily over the insistent wind. “Space-defense must have tracked him on radar.”

“Nope. If they’d hit him from orbit, he’d really be spread all over. . . . No, something happened to him really close to the ground.”

Pete pointed at a violent scattering of cracked ochre rock. “See, check out how that stealth-pod hit and tumbled. It didn’t catch fire till after the impact.”

With the absent ease of a gecko, the neuter swarmed up a three-story-high boulder. She examined the surrounding forensic evidence at length, dabbing carefully at her spex controls. She then slithered deftly back to earth.

“There was no anti-aircraft fire, right? No interceptors flyin’ round last night.”

“Nope. Heck, there’s no people around here in a space bigger than Delaware.”

The neuter looked up. “So what do you figure, Pete?”

“I figure an accident,” said Pete.

“A what?”

“An accident. A lot can go wrong with a covert HALO insertion.”

“Like what, for instance?”

“Well, G-loads and stuff. System malfunctions. Maybe he just blacked out.”

“He was a federal military spook, and you’re telling me he passed out?” Katrinko daintily adjusted her goggled spex with gloved and bulbous fingertips. “Why would that matter anyway? He wouldn’t fly a spacecraft with his own hands, would he?”

Pete rubbed at the gummy line of his mask, easing the prickly indentation across one dark, tattooed cheek. “I kinda figure he would, actually. The man was a pilot. Big military prestige thing. Flyin’ in by hand, deep in Sphere territory, covert insertion, way behind enemy lines. . . . That’d really be something to brag about, back on the Potomac.”

The neuter considered this sour news without apparent resentment. As one of the world’s top technical climbers, Katrinko was a great connoisseur of pointless displays of dangerous physical skill.

“I can get behind that.” She paused. “Serious bad break, though.”

They resealed their masks. Water was their greatest lack, and vapor exhalation was a problem. They were recycling body-water inside their suits, topped off with a few extra cc’s they’d obtained from occasional patches of frost. They’d consumed the last of the trail-goop and candy from their glider shipment three long days ago. They hadn’t eaten since. Still, Pete and Katrinko were getting along pretty well, living off big subcutaneous lumps of injected body fat.

More through habit than apparent need, Pete and Katrinko segued into evidence-removal mode. It wasn’t hard to conceal a HALO stealth pod. The spycraft was radar-transparent and totally biodegradable. In the bitter wind and cold of the Taklamakan, the bigger chunks of wreckage had already gone all brown and crispy, like the shed husks of locusts. They couldn’t scrape up every physical trace, but they’d surely get enough to fool aerial surveillance.

The Lieutenant Colonel was extremely dead. He’d come down from the heavens in his full NAFTA military power-armor, a leaping, brick-busting, lightning-spewing exoskeleton, all acronyms and input jacks. It was powerful, elaborate gear, of an entirely different order than the gooey and fibrous street tech of the two urban intrusion freaks. But the high-impact crash had not been kind to the armored suit. It had been crueler still to the bone, blood, and tendon housed inside. Pete bagged the larger pieces with a heavy heart. He knew that the Lieutenant Colonel was basically no good: deceitful, ruthlessly ambitious, probably crazy. Still, Pete sincerely regretted his employer’s demise. After all, it was precisely those qualities that had led the Lieutenant Colonel to recruit Spider Pete in the first place.

Pete also felt sincere regret for the gung-ho, clear-eyed young military widow, and the two little redheaded kids in Augusta, Georgia. He’d never actually met the widow or the little kids, but the Lieutenant Colonel was always fussing about them and showing off their photos. The Lieutenant Colonel had been a full fifteen years younger than Spider Pete, a rosy-cheeked cracker kid really, never happier than when handing over wads of money, nutty orders, and expensive covert equipment to people whom no sane man would trust with a burnt-out match. And now here he was in the cold and empty heart of Asia, turned to jam within his shards of junk. Katrinko did the last of the search-and-retrieval while Pete dug beneath a ledge with his diamond hand-pick, the razored edges slashing out clods of shale.

After she’d fetched the last blackened chunk of their employer, Katrinko perched birdlike on a nearby rock. She thoughtfully nibbled a piece of the pod’s navigation console. “This gelbrain is good when it dries out, man. Like trail mix, or a fortune cookie.”

Pete grunted. “You might be eating part of him, y’know.”

“Lotta good carbs and protein there, too.”

They stuffed a final shattered power-jackboot inside the Colonel’s makeshift cairn. The piled rock was there for the ages. A few jets of webbing and thumbnail dabs of epoxy made it harder than a brick wall. It was noon now, still well below freezing, but as warm as the Taklamakan was likely to get in January. Pete sighed, dusted sand from his knees and elbows, stretched. It was hard work, cleaning up; the hardest part of intrusion work, because it was the stuff you had to do after the thrill was gone. He offered Katrinko the end of a fiber-optic cable, so that they could speak together without using radio or removing their masks.

Pete waited until she had linked in, then spoke into his mike. “So we head on back to the glider now, right?”

The neuter looked up, surprised. “How come?”

“Look, Trink, this guy that we just buried was the actual spy in this assignment. You and me, we were just his gophers and backup support. The mission’s an abort.”

“But we’re searching for a giant, secret, rocket base.”

“Yeah, sure we are.”

“We’re supposed to find this monster high-tech complex, break in, and record all kinds of crazy top secrets that nobody but the mandarins have ever seen. That’s a totally hot assignment, man.”

Pete sighed. “I admit it’s very high-concept, but I’m an old guy now, Trink. I need the kind of payoff that involves some actual money.”

Katrinko laughed. “But Pete! It’s a starship! A whole fleet of ’em, maybe! Secretly built in the desert, by Chinese spooks and Japanese engineers!”

Pete shook his head. “That was all paranoid bullshit that the flyboy made up, to get himself a grant and a field assignment. He was tired of sitting behind a desk in the basement, that’s all.”

Katrinko folded her lithe and wiry arms. “Look, Pete, you saw those briefings just like me. You saw all those satellite shots. The traffic analysis, too. The Sphere people are up to something way big out here.”

Pete gazed around him. He found it painfully surreal to endure this discussion amid a vast and threatening tableau of dust-hazed sky and sand-etched mudstone gullies. “They built something big here once, I grant you that. But I never figured the Colonel’s story for being very likely.”

“What’s so unlikely about it? The Russians had a secret rocket base in the desert a hundred years ago. American deserts are full of secret mil-spec stuff and space-launch bases. So now the Asian Sphere people are up to the same old game. It all makes sense.”

“No, it makes no sense at all. Nobody’s space-racing to build any starships. Starships aren’t a space race. It takes four hundred years to fly to the stars. Nobody’s gonna finance a major military project that’ll take four hundred years to pay off. Least of all a bunch of smart and thrifty Asian economic-warfare people.”

“Well, they’re sure building something. Look, all we have to do is find the complex, break in, and document some stuff. We can do that! People like us, we never needed any federal bossman to help us break into buildings and take photos. That’s what we always do, that’s what we live for.”

Pete was touched by the kid’s game spirit. She really had the City Spider way of mind. Nevertheless, Pete was fifty-two years old, so he found it necessary to at least try to be reasonable. “We should haul our sorry spook asses back to that glider right now. Let’s skip on back over the Himalayas. We can fly on back to Washington, tourist class out of Delhi. They’ll debrief us at the puzzle-palace. We’ll give ’em the bad news about the bossman. We got plenty of evidence to prove that, anyhow. . . . The spooks will give us some walkin’ money for a busted job, and tell us to keep our noses clean. Then we can go out for some pork chops.”

Katrinko’s thin shoulders hunched mulishly within the bubblepak warts of her insulated camou. She was not taking this at all well. “Peter, I ain’t looking for pork chops. I’m looking for some professional validation, okay? I’m sick of that lowlife kid stuff, knocking around raiding network sites and mayors’ offices. . . . This is my chance at the big-time!”

Pete stroked the muzzle of his mask with two gloved fingers.

“Pete, I know that you ain’t happy. I know that already, okay? But you’ve already made it in the big-time, Mr. City Spider, Mr. Legend, Mr. Champion. Now here’s my big chance come along, and you want us to hang up our cleats.”

Pete raised his other hand. “Wait a minute, I never said that.”

“Well, you’re tellin’ me you’re walking. You’re turning your back. You don’t even want to check it out first.”

“No,” Pete said weightily, “I reckon you know me too well for that, Trink. I’m still a Spider. I’m still game. I’ll always at least check it out.”

Katrinko set their pace after that. Pete was content to let her lead. It was a very stupid idea to continue the mission without the overlordship of the Lieutenant Colonel. But it was stupid in a different and more refreshing way than the stupid idea of returning home to Chattanooga. People in Pete’s line of work weren’t allowed to go home. He’d tried that once, really tried it, eight years ago, just after that badly busted caper in Brussels. He’d gotten a straight job at Lyle Schweik’s pedal-powered aircraft factory. The millionaire sports tycoon had owed him a favor. Schweik had been pretty good about it, considering. But word had swiftly gotten around that Pete had once been a champion City Spider. Dumb-ass co-workers would make significant remarks. Sometimes they asked him for so-called “favors,” or tried to act street-wise. When you came down to it, straight people were a major pain in the ass. Pete preferred the company of seriously twisted people. People who really cared about something, cared enough about it to really warp themselves for it. People who looked for more out of life than mommy-daddy, money, and the grave.

Below the edge of a ridgeline they paused for a recce. Pete whirled a tethered eye on the end of its reel and flung it. At the peak of its arc, six stories up, it recorded their surroundings in a panoramic view. Pete and Katrinko studied the image together through their linked spex. Katrinko highlit an area downhill with a fingertip gesture. “Now there’s a tipoff.”

“That gully, you mean?”

“You need to get outdoors more, Pete. That’s what we rockjocks technically call a road.”

Pete and Katrinko approached the road with professional caution. It was a paved ribbon of macerated cinderblock, overrun with drifting sand. The road was made of the coked-out clinker left behind by big urban incinerators, a substance that Asians used for their road surfaces because all the value had been cooked out of it. The cinder road had once seen a great deal of traffic. There were tire-shreds here and there, deep ruts in the shoulder, and post-holes that had once been traffic signs, or maybe surveillance boxes. They followed the road from a respectful distance, cautious of monitors, tripwires, landmines, and many other possible unpleasantries. They stopped for a rest in a savage arroyo where a road bridge had been carefully removed, leaving only neat sockets in the roadbed and a kind of conceptual arc in midair.

“What creeps me out is how clean this all is,” Pete said over cable. “It’s a road, right? Somebody’s gotta throw out a beer can, a lost shoe, something.”

Katrinko nodded. “I figure construction robots.”

“Really.”

Katrinko spread her swollen-fingered gloves. “It’s a Sphere operation, so it’s bound to have lots of robots, right? I figure robots built this road. Robots used this road. Robots carried in tons and tons of whatever they were carrying. Then when they were done with the big project, the robots carried off everything that was worth any money. Gathered up the guideposts, bridges, everything. Very neat, no loose ends, very Sphere-type way to work.”

Katrinko set her masked chin on her bent knees, gone into reverie. “Some very weird and intense stuff can happen, when you got a lot of space in the desert, and robot labor that’s too cheap to meter.”Katrinko hadn’t been wasting her time in those intelligence briefings. Pete had seen a lot of City Spider wannabes, even trained quite a few of them. But Katrinko had what it took to be a genuine Spider champion: the desire, the physical talent, the ruthless dedication, and even the smarts. It was staying out of jails and morgues that was gonna be the tough part for Katrinko.

“You’re a big fan of the Sphere, aren’t you, kid? You really like the way they operate.”

“Sure, I always liked Asians. Their food’s a lot better than Europe’s.”

Pete took this in stride. NAFTA, Sphere, and Europe: the trilateral superpowers jostled about with the uneasy regularity of sunspots, periodically brewing storms in the proxy regimes of the South. During his fifty-plus years, Pete had seen the Asian Cooperation Sphere change its public image repeatedly, in a weird political rhythm. Exotic vacation spot on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Baffling alien threat on Mondays and Wednesdays. Major trading partner each day and every day, including weekends and holidays. At the current political moment, the Asian Cooperation Sphere was deep into its Inscrutable Menace mode, logging lots of grim media coverage as NAFTA’s chief economic adversary. As far as Pete could figure it, this basically meant that a big crowd of goofy North American economists were trying to act really macho. Their major complaint was that the Sphere was selling NAFTA too many neat, cheap, well-made consumer goods. That was an extremely silly thing to get killed about. But people perished horribly for much stranger reasons than that.

At sunset, Pete and Katrinko discovered the giant warning signs. They were titanic vertical plinths, all epoxy and clinker, much harder than granite. They were four stories tall, carefully rooted in bedrock, and painstakingly chiseled with menacing horned symbols and elaborate textual warnings in at least fifty different languages. English was language number three.

“Radiation waste,” Pete concluded, deftly reading the text through his spex, from two kilometers away. “This is a radiation waste dump. Plus, a nuclear test site. Old Red Chinese hydrogen bombs, way out in the Taklamakan desert.” He paused thoughtfully. “You gotta hand it to ’em. They sure picked the right spot for the job.”

“No way!” Katrinko protested. “Giant stone warning signs, telling people not to trespass in this area? That’s got to be a con-job.”

“Well, it would sure account for them using robots, and then destroying all the roads.”

“No, man. It’s like–you wanna hide something big nowadays. You don’t put a safe inside the wall any more, because hey, everybody’s got magnetometers and sonic imaging and heat detection. So you hide your best stuff in the garbage.”

Pete scanned their surroundings on spex telephoto. They were lurking on a hillside above a playa, where the occasional gullywasher had spewed out a big alluvial fan of desert-varnished grit and cobbles. Stuff was actually growing down there–squat leathery grasses with fat waxy blades like dead men’s fingers. The evil vegetation didn’t look like any kind of grass that Pete had ever seen. It struck him as the kind of grass that would blithely gobble up stray plutonium.

“Trink, I like my explanations simple. I figure that so-called giant starship base for a giant radwaste dump.”

“Well, maybe,” the neuter admitted. “But even if that’s the truth, that’s still news worth paying for. We might find some busted-up barrels, or some badly managed fuel rods out there. That would be a big political embarrassment, right? Proof of that would be worth something.”

“Huh,” said Pete, surprised. But it was true. Long experience had taught Pete that there were always useful secrets in other people’s trash. “Is it worth glowin’ in the dark for?”

“So what’s the problem?” Katrinko said. “I ain’t having kids. I fixed that a long time ago. And you’ve got enough kids already.”

“Maybe,” Pete grumbled. Four kids by three different women. It had taken him a long sad time to learn that women who fell head-over-heels for footloose, sexy tough guys would fall repeatedly for pretty much any footloose, sexy tough guy.

Katrinko was warming to the task at hand. “We can do this, man. We got our suits and our breathing masks, and we’re not eating or drinking anything out here, so we’re practically radiation-tight. So we camp way outside the dump tonight. Then before dawn we slip in, we check it out real quick, we take our pictures, we leave. Clean, classic intrusion job. Nobody living around here to stop us, no problem there. And then, we got something to show the spooks when we get home. Maybe something we can sell.”

Pete mulled this over. The prospect didn’t sound all that bad. It was dirty work, but it would complete the mission. Also–this was the part he liked best–it would keep the Lieutenant Colonel’s people from sending in some other poor guy. “Then, back to the glider?”

“Then back to the glider.”

“Okay, good deal.”

Before dawn the next morning, they stoked themselves with athletic performance enhancers, brewed in the guts of certain gene-spliced ticks that they had kept hibernating in their armpits. Then they concealed their travel gear, and swarmed like ghosts up and over the great wall. They pierced a tiny hole through the roof of one of the duncolored, half-buried containment hangars, and oozed a spy-eye through. Bombproofed ranks of barrel-shaped sarcophagi, solid and glossy as polished granite. The big fused radwaste containers were each the size of a tanker truck. They sat there neatly ranked in hermetic darkness, mute as sphinxes. They looked to be good for the next twenty thousand years.

Pete liquefied and retrieved the gelcam, then re-sealed the tiny hole with rock putty. They skipped down the slope of the dusty roof. There were lots of lizard tracks in the sand drifts, piled at the rim of the dome. These healthy traces of lizard cheered Pete up considerably. They swarmed silently up and over the wall. Back uphill to the grotto where they’d stashed their gear. Then they removed their masks to talk again. Pete sat behind a boulder, enjoying the intrusion after-glow.

“A cakewalk,” he pronounced it. “A pleasure hike.” His pulse was already normal again, and, to his joy, there were no suspicious aches under his caraco-acromial arch.

“You gotta give them credit, those robots sure work neat.”

Pete nodded. “Killer application for robots, your basic lethal waste gig.”

“I telephoto’ed that whole cantonment,” said Katrinko, “and there’s no water there. No towers, no plumbing, no wells. People can get along without a lot of stuff in the desert, but nobody lives without water. That place is stone dead. It was always dead.” She paused. “It was all automated robot work from start to finish. You know what that means, Pete? It means no human being has ever seen that place before. Except for you and me.”

“Hey, then it’s a first! We scored a first intrusion! That’s just dandy,” said Pete, pleased at the professional coup. He gazed across the cobbled plain at the walled cantonment, and pressed a last set of spex shots into his gelbrain archive. Two dozen enormous domes, built block by block by giant robots, acting with the dumb persistence of termites. The sprawling domes looked as if they’d congealed on the spot, their rims settling like molten taffy into the desert’s little convexities and concavities. From a satellite view, the domes probably passed for natural features.

“Let’s not tarry, okay? I can kinda feel those X-ray fingers kinking my DNA.”

“Aw, you’re not all worried about that, are you, Pete?”

Pete laughed and shrugged. “Who cares? Job’s over, kid. Back to the glider.”

“They do great stuff with gene damage nowadays, y’know. Kinda re-weave you, down at the spook lab.”

“What, those military doctors? I don’t wanna give them the excuse.”The wind picked up. A series of abrupt and brutal gusts. Dry, and freezing, and peppered with stinging sand. Suddenly, a faint moan emanated from the cantonment. Distant lungs blowing the neck of a wine bottle.

“What’s that big weird noise?” demanded Katrinko, all alert interest.

“Aw no,” said Pete. “Dang.”

Steam was venting from a hole in the bottom of the thirteenth dome. They’d missed the hole earlier, because the rim of that dome was overgrown with big thriving thornbushes. The bushes would have been a tip-off in themselves, if the two of them had been feeling properly suspicious. In the immediate area, Pete and Katrinko swiftly discovered three dead men. The three men had hacked and chiseled their way through the containment dome–from the inside. They had wriggled through the long, narrow crevice they had cut, leaving much blood and skin. The first man had died just outside the dome, apparently from sheer exhaustion. After their Olympian effort, the two survivors had emerged to confront the sheer four-story walls. The remaining men had tried to climb the mighty wall with their handaxes, crude woven ropes, and pig-iron pitons. It was a nothing wall for a pair of City Spiders with modern handwebs and pinpression cleats. Pete and Katrinko could have camped and eaten a watermelon on that wall. But it was a very serious wall for a pair of very weary men dressed in wool, leather, and homemade shoes. One of them had fallen from the wall, and had broken his back and leg. The last one had decided to stay to comfort his dying comrade, and it seemed he had frozen to death. The three men had been dead for many months, maybe over a year. Ants had been at work on them, and the fine salty dust of the Taklamakan, and the freeze-drying. Three desiccated Asian mummies, black hair and crooked teeth and wrinkled dusky skin, in their funny bloodstained clothes.

Katrinko offered the cable lead, chattering through her mask. “Man, look at these shoes! Look at this shirt this guy’s got–would you call this thing a shirt?”

“What I would call this is three very brave climbers,” Pete said.

He tossed a tethered eye into the crevice that the men had cut. The inside of the thirteenth dome was a giant forest of monitors. Microwave antennas, mostly. The top of the dome wasn’t sturdy sintered concrete like the others, it was some kind of radar-transparent plastic. Dark inside, like the other domes, and hermetically sealed–at least before the dead men had chewed and chopped their hole through the wall.

No sign of any radwaste around here.

They discovered the little camp where the men had lived. Their bivouac. Three men, patiently chipping and chopping their way to freedom. Burning their last wicks and oil lamps, eating their last rations bite by bite, emptying their leather canteens and scraping for frost to drink. Surrounded all the time by a towering jungle of satellite relays and wavepipes. Pete found that scene very ugly. That was a very bad scene. That was the worst of it yet.

Pete and Katrinko retrieved their full set of intrusion gear. They then broke in through the top of the dome, where the cutting was easiest. Once through, they sealed the hole behind themselves, but only lightly, in case they should need a rapid retreat. They lowered their haul bags to the stone floor, then rappelled down on their smart ropes. Once on ground level, they closed the escape tunnel with web and rubble, to stop the howling wind, and to keep contaminants at bay.

With the hole sealed, it grew warmer in the dome. Warm, and moist. Dew was collecting on walls and floor. A very strange smell, too. A smell like smoke and old socks. Mice and spice. Soup and sewage. A cozy human reek from the depths of the earth.

“The Lieutenant Colonel sure woulda have loved this,” whispered Katrinko over cable, spexing out the towering machinery with her infrareds. “You put a clip of explosive ammo through here, and it sure would put a major crimp in somebody’s automated gizmos.”

Pete figured their present situation for an excellent chance to get killed. Automated alarm systems were the deadliest aspect of his professional existence, somewhat tempered by the fact that smart and aggressive alarm systems frequently killed their owners. There was a basic engineering principle involved. Fancy, paranoid alarm systems went false-positive all the time: squirrels, dogs, wind, hail, earth tremors, horny boyfriends who forgot the password. . . . They were smart, and they had their own agenda, and it made them troublesome.

But if these machines were alarms, then they hadn’t noticed a rather large hole painstakingly chopped in the side of their dome. The spars and transmitters looked bad, all patchy with long-accumulated rime and ice. A junkyard look, the definite smell of dead tech. So somebody had given up on these smart, expensive, paranoid alarms. Someone had gotten sick and tired of them, and shut them off.

At the foot of a microwave tower, they found a rat-sized manhole chipped out, covered with a laced-down lid of sheep’s hide. Pete dropped a spy-eye down, scoping out a machine-drilled shaft. The tunnel was wide enough to swallow a car, and it dropped down as straight as a plumb bob for farther than his eye’s wiring could reach. Pete silently yanked a rusting pig-iron piton from the edge of the hole, and replaced it with a modern glue anchor. Then he whipped a smart-rope through and carefully tightened his harness.

Katrinko began shaking with eagerness. “Pete, I am way hot for this. Lemme lead point.”

Pete clipped a crab into Katrinko’s harness, and linked their spex through the fiber-optic embedded in the rope. Then he slapped the neuter’s shoulder.

“Get bold, kid.”

Katrinko flared out the webbing on her gripgloves, and dropped in feetfirst. The would-be escapees had made a lot of use of cabling already present in the tunnel. There were ceramic staples embedded periodically, to hold the cabling snug against the stone. The climbers had scrabbled their way up from staple to staple, using ladder-runged bamboo poles and iron hooks.

Katrinko stopped her descent and tied off. Pete sent their haulbags down. Then he dropped and slithered after her. He stopped at the lead chock, tied off, and let Katrinko take lead again, following her progress with the spex. An eerie glow shone at the bottom of the tunnel. Pay day. Pete felt a familiar transcendental tension overcome him. It surged through him with mad intensity. Fear, curiosity, and desire: the raw, hot, thieving thrill of a major-league intrusion. A feeling like being insane, but so much better than craziness, because now he felt so awake. Pete was awash in primal spiderness, cravings too deep and slippery to speak about.The light grew hotter in Pete’s infrareds. Below them was a slotted expanse of metal, gleaming like a kitchen sink, louvers with hot slots of light.

Katrinko planted a foamchock in the tunnel wall, tied off, leaned back, and dropped a spy eye through the slot.

Pete’s hands were too busy to reach his spex. “What do you see?” he hissed over cable.

Katrinko craned her head back, gloved palms pressing the goggles against her face. “I can see everything, man! Gardens of Eden, and cities of gold!”

The cave had been ancient solid rock once, a continental bulk. The rock had been pierced by a Russian-made drilling rig. A dry well, in a very dry country. And then some very weary, and very sunburned, and very determined Chinese Communist weapons engineers had installed a one-hundred megaton hydrogen bomb at the bottom of their dry hole. When their beast in its nest of layered casings achieved fusion, seismographs jumped like startled fawns in distant California.

The thermonuclear explosion had left a giant gasbubble at the heart of a crazy webwork of faults and cracks. The deep and empty bubble had lurked beneath the desert in utter and terrible silence, for ninety years.

Then Asia’s new masters had sent in new and more sophisticated agencies.

Pete saw that the distant sloping walls of the cavern were daubed with starlight. White constellations, whole and entire. And amid the space–that giant and sweetly damp airspace–were three great glowing lozenges, three vertical cylinders the size of urban high rises. They seemed to be suspended in midair.

“Starships,” Pete muttered.

“Starships,” Katrinko agreed. Menus appeared in the shared visual space of their linked spex. Katrinko’s fingertip sketched out a set of tiny moving sparks against the walls. “But check that out.”

“What are those?”

“Heat signatures. Little engines.” The envisioned world wheeled silently. “And check out over here too–and crawlin’ around deep in there, dozens of the things. And Pete, see these? Those big ones? Kinda on patrol?”

“Robots.”

“Yep.”

“What the hell are they up to, down here?”

“Well, I figure it this way, man. If you’re inside one of those fake starships, and you look out through those windows–those portholes, I guess we call ’em–you can’t see anything but shiny stars. Deep space. But with spex, we can see right through all that business. And Pete, that whole stone sky down there is crawling with machinery.”

“Man oh man.”

“And nobody inside those starships can see down, man. There is a whole lot of very major weirdness going on down at the bottom of that cave. There’s a lot of hot steamy water down there, deep in those rocks and those cracks.”

“Water, or a big smelly soup maybe,” Pete said. “A chemical soup.”

“Biochemical soup.”

“Autonomous self-assembly proteinaceous biotech. Strictly forbidden by the Nonproliferation Protocols of the Manila Accords of 2037,” said Pete. Pete rattled off this phrase with practiced ease, having rehearsed it any number of times during various background briefings. “A whole big lake of way-hot, way-illegal, self-assembling goo down there.”

“Yep. The very stuff that our covert-tech boys have been messing with under the Rockies for the past ten years.”

“Aw, Pete, everybody cheats a little bit on the accords. The way we do it in NAFTA, it’s no worse than bathtub gin. But this is huge! And Lord only knows what’s inside those starships.”

“Gotta be people, kid.”

“Yep.” Pete drew a slow moist breath. “This is a big one, Trink. This is truly major-league. You and me, we got ourselves an intelligence coup here of historic proportions.”

“If you’re trying to say that we should go back to the glider now,” Katrinko said, “don’t even start with me.”

“We need to go back to the glider,” Pete insisted, “with the photographic proof that we got right now. That was our mission objective. It’s what they pay us for.”

“Whoop-tee-do.”

“Besides, it’s the patriotic thing. Right?”

“Maybe I’d play the patriot game, if I was in uniform,” said Katrinko. “But the Army don’t allow neuters. I’m a total freak and I’m a free agent, and I didn’t come here to see Shangri-La and then turn around first thing.”

“Yeah,” Pete admitted. “I really know that feeling.”

“I’m going down in there right now,” Katrinko said. “You belay for me?”

“No way, kid. This time, I’m leading point.”

Pete eased himself through a crudely broken louver and out onto the vast rocky ceiling. Pete had never much liked climbing rock. Nasty stuff, rock–all natural, no guaranteed engineering specifications. Still, Pete had spent a great deal of his life on ceilings. Ceilings he understood.

He worked his way out on a series of congealed lava knobs, till he hit a nice solid crack. He did a rapid set of fist-jams, then set a pair of foam-clamps, and tied himself off on anchor. Pete panned slowly in place, upside down on the ceiling, muffled in his camou gear, scanning methodically for the sake of Katrinko back on the fiber-optic spex link. Large sections of the ceiling looked weirdly worm-eaten, as if drills or acids had etched the rock away. Pete could discern in the eerie glow of infrared that the three fake starships were actually supported on columns. Huge hollow tubes, lacelike and almost entirely invisible, made of something black and impossibly strong, maybe carbon-fiber. There were water pipes inside the columns, and electrical power.

Those columns were the quickest and easiest ways to climb down or up to the starships. Those columns were also very exposed. They looked like excellent places to get killed. Pete knew that he was safely invisible to any naked human eye, but there wasn’t much he could do about his heat signature. For all he knew, at this moment he was glowing like a Christmas tree on the sensors of a thousand heavily armed robots. But you couldn’t leave a thousand machines armed to a hair-trigger for years on end. And who would program them to spend their time watching ceilings? The muscular burn had faded from his back and shoulders. Pete shook a little extra blood through his wrists, unhooked, and took off on cleats and gripwebs. He veered around one of the fake stars, a great glowing glassine bulb the size of a laundry basket. The fake star was cemented into a big rocky wart, and it radiated a cold, enchanting, and gooey firefly light. Pete was so intrigued by this bold deception that his cleat missed a smear. His left foot swung loose. His left shoulder emitted a nasty-feeling, expensive-sounding pop. Pete grunted, planted both cleats, and slapped up a glue patch, with tendons smarting and the old forearm clock ticking fast. He whipped a crab through the patchloop and sagged within his harness, breathing hard.

On the surface of his spex, Katrinko’s glowing fingertip whipped across the field of Pete’s vision, and pointed. Something moving out there. Pete had company.

Pete eased a string of flashbangs from his sleeve. Then he hunkered down in place, trusting to his camouflage, and watching.

A robot was moving toward him among the dark pits of the fake stars. Wobbling and jittering.

Pete had never seen any device remotely akin to this robot. It had a porous, foamy hide, like cork and plastic. It had a blind compartmented knob for a head, and fourteen long fibrous legs like a frayed mess of used rope, terminating in absurdly complicated feet, like a boxful of grip pliers. Hanging upside down from bits of rocky irregularity too small to see, it would open its big warty head and flick out a forked sensor like a snake’s tongue. Sometimes it would dip itself close to the ceiling, for a lingering chemical smooch on the surface of the rock.

Pete watched with murderous patience as the device backed away, drew nearer, spun around a bit, meandered a little closer, sucked some more ceiling rock, made up its mind about something, replanted its big grippy feet, hoofed along closer yet, lost its train of thought, retreated a bit, sniffed the air at length, sucked meditatively on the end of one of its ropy tentacles.

It finally reached him, walked deftly over his legs, and dipped up to lick enthusiastically at the chemical traces left by his gripweb. The robot seemed enchanted by the taste of the glove’s elastomer against the rock. It hung there on its fourteen plier feet, loudly licking and rasping.

Pete lashed out with his pick. The razored point slid with a sullen crunch right through the thing’s corky head. It went limp instantly, pinned there against the ceiling. Then with a nasty rustling it deployed a whole unsuspected set of waxy and filmy appurtenances. Complex bug-tongue things, mandible scrapers, delicate little spatulas, all reeling and trembling out of its slotted underside.

It was not going to die. It couldn’t die, because it had never been alive. It was a piece of biotechnical machinery. Dying was simply not on its agenda anywhere. Pete photographed the device carefully as it struggled with obscene mechanical stupidity to come to workable terms with its new environmental parameters. Then Pete levered the pick loose from the ceiling, shook it loose, and dropped the pierced robot straight down to hell.

Pete climbed more quickly now, favoring the strained shoulder. He worked his way methodically out to the relative ease of the vertical wall, where he discovered a large mined-out vein in the constellation Sagittarius. The vein was a big snaky recess where some kind of ore had been nibbled and strained from the rock. By the look of it, the rock had been chewed away by a termite host of tiny robots with mouths like toenail clippers.He signaled on the spex for Katrinko. The neuter followed along the clipped and anchored line, climbing like a fiend while lugging one of the haulbags. As Katrinko settled in to their new base camp, Pete returned to the louvers to fetch the second bag. When he’d finally heaved and grappled his way back, his shoulder was aching bitterly and his nerves were shot. They were done for the day.

Katrinko had put up the emission-free encystment web at the mouth of their crevice. With Pete returned to relative safety, she reeled in their smart-ropes and fed them a handful of sugar. Pete cracked open two capsules of instant fluff, then sank back gratefully into the wool. Katrinko took off her mask. She was vibrating with alert enthusiasm. Youth, thought Pete–youth, and the 8 percent metabolic advantage that came from lacking sex organs.

“We’re in so much trouble now,” Katrinko whispered, with a feverish grin in the faint red glow of a single indicator light. She no longer resembled a boy or a young woman. Katrinko looked completely diabolical.

This was a nonsexed creature. Pete liked to think of her as a “she,” because this was somehow easier on his mind, but Katrinko was an “it.” Now it was filled with glee, because finally it had placed itself in a proper and pleasing situation. Stark and feral confrontation with its own stark and feral little being.

“Yeah, this is trouble,” Pete said. He placed a fat medicated tick onto the vein inside of his elbow. “And you’re taking first watch.”

Pete woke four hours later, with a heart-fluttering rise from the stunned depths of chemically assisted delta-sleep. He felt numb, and lightly dusted with a brain-clouding amnesia, as if he’d slept for four straight days. He had been profoundly helpless in the grip of the drug, but the risk had been worth it, because now he was thoroughly rested. Pete sat up, and tried the left shoulder experimentally. It was much improved.

Pete rubbed feeling back into his stubbled face and scalp, then strapped his spex on. He discovered Katrinko squatting on her haunches, in the radiant glow of her own body heat, pondering over an ugly mess of spines, flakes, and goo.

Pete touched spex knobs and leaned forward. “What you got there?”

“Dead robots. They ate our foamchocks, right out of the ceiling. They eat anything. I killed the ones that tried to break into camp.” Katrinko stroked at a midair menu, then handed Pete a fiber lead for his spex. “Check this footage I took.”

Katrinko had been keeping watch with the gelcams, picking out passing robots in the glow of their engine heat. She’d documented them on infrared, saving and editing the clearest live-action footage. “These little ones with the ball-shaped feet, I call them keets,” she narrated, as the captured frames cascaded across Pete’s spex-clad gaze. “They’re small, but they’re really fast, and all over the place–I had to kill three of them. This one with the sharp spiral nose is a drillet. Those are a pair of dubits. The dubits always travel in pairs. This big thing here, that looks like a spilled dessert with big eyes and a ball on a chain, I call that one a lurchen. Because of the way it moves, see? It’s sure a lot faster than it looks.”

Katrinko stopped the spex replay, switched back to live perception, and poked carefully at the broken litter before her booted feet. The biggest device in the heap resembled a dissected cat’s head stuffed with cables and bristles. “I also killed this piteen. Piteens don’t die easy, man.”

“There’s lots of these things?”

“I figure hundreds, maybe thousands. All different kinds. And every one of ’em as stupid as dirt. Or else we’d be dead and disassembled a hundred times already.”

Pete stared at the dissected robots, a cooling mass of nerve-netting, batteries, veiny armor plates, and gelatin.

“Why do they look so crazy?”

“’Cause they grew all by themselves. Nobody ever designed them.”

Katrinko glanced up. “You remember those big virtual spaces for weapons design, that they run out in Alamagordo?”

“Yeah, sure, Alamagordo. Physics simulations on those super-size quantum gelbrains. Huge virtualities, with ultra-fast, ultra-fine detail. You bet I remember New Mexico! I love to raid a great computer lab. There’s something so traditional about the hack.”

“Yeah. See, for us NAFTA types, physics virtualities are a military app. We always give our tech to the military whenever it looks really dangerous. But let’s say you don’t share our NAFTA values. You don’t wanna test new weapons systems inside giant virtualities. Let’s say you want to make a can-opener, instead.”

During her sleepless hours huddling on watch, Katrinko had clearly been giving this matter a lot of thought.

“Well, you could study other people’s can-openers and try to improve the design. Or else you could just set up a giant high-powered virtuality with a bunch of virtual cans inside it. Then you make some can-opener simulations, that are basically blobs of goo. They’re simulated goo, but they’re also programs, and those programs trade data and evolve. Whenever they pierce a can, you reward them by making more copies of them. You’re running, like, a million generations of a million different possible can-openers, all day every day, in a simulated space.”

The concept was not entirely alien to Spider Pete. “Yeah, I’ve heard the rumors. It was one of those stunts like Artificial Intelligence. It might look really good on paper, but you can’t ever get it to work in real life.”

“Yeah, and now it’s illegal too. Kinda hard to police, though. But let’s imagine you’re into economic warfare and you figure out how to do this. Finally, you evolve this super weird, super can-opener that no human being could ever have invented. Something that no human being could even imagine. Because it grew like a mushroom in an entire alternate physics. But you have all the specs for its shape and proportions, right there in the supercomputer. So to make one inside the real world, you just print it out like a photograph. And it works! It runs! See? Instant cheap consumer goods.”

Pete thought it over. “So you’re saying the Sphere people got that idea to work, and these robots here were built that way?”

“Pete, I just can’t figure any other way this could have happened. These machines are just too alien. They had to come from some totally nonhuman, autonomous process. Even the best Japanese engineers can’t design a jelly robot made out of fuzz and rope that can move like a caterpillar. There’s not enough money in the world to pay human brains to think that out.”

Pete prodded at the gooey ruins with his pick. “Well, you got that right.”

“Whoever built this place, they broke a lot of rules and treaties. But they did it all really cheap. They did it in a way that is so cheap that it is beyond economics.”

Katrinko thought this over. “It’s way beyond economics, and that’s exactly why it’s against all those rules and the treaties in the first place.”

“Fast, cheap, and out of control.”

“Exactly, man. If this stuff ever got loose in the real world, it would mean the end of everything we know.”

Pete liked this last statement not at all. He had always disliked apocalyptic hype. He liked it even less now because under these extreme circumstances it sounded very plausible. The Sphere had the youngest and the biggest population of the three major trading blocs, and the youngest and the biggest ideas. People in Asia knew how to get things done.

“Y’know, Lyle Schweik once told me that the weirdest bicycles in the world come out of China these days.”

“Well, he’s right. They do. And what about those Chinese circuitry chips they’ve been dumping in the NAFTA markets lately? Those chips are dirt cheap and work fine, but they’re full of all this crazy leftover wiring that doubles back and gets all snarled up. . . . I always thought that was just shoddy workmanship. Man, ‘workmanship’ had nothing to do with those chips.”

Pete nodded soberly. “Okay. Chips and bicycles, that much I can understand. There’s a lot of money in that. But who the heck would take the trouble to create a giant hole in the ground that’s full of robots and fake stars? I mean, why?”

Katrinko shrugged. “I guess it’s just the Sphere, man. They still do stuff just because it’s wonderful.”

The bottom of the world was boiling over. During the passing century, the nuclear test cavity had accumulated its own little desert aquifer, a pitch-black subterranean oasis. The bottom of the bubble was an unearthly drowned maze of shattered cracks and chemical deposition, all turned to simmering tidepools of mechanical self-assemblage.

Oxygen-fizzing geysers of black fungus tea.

Steam rose steadily in the darkness amid the crags, rising to condense and run in chilly rivulets down the spherical star-spangled walls. Down at the bottom, all the water was eagerly collected by aberrant devices of animated sponge and string. Katrinko instantly tagged these as “smits” and “fuzzens.”

The smits and fuzzens were nightmare dishrags and piston-powered spaghetti, leaping and slopping wetly from crag to crag. Katrinko took an unexpected ease and pleasure in naming and photographing the machines. Speculation boiled with sinister ease from the sexless youngster’s vulpine head, a swift off-the-cuff adjustment to this alien toy world. It would seem that the kid lived rather closer to the future than Pete did.

They cranked their way from boulder to boulder, crack to liquid crack. They documented fresh robot larvae, chewing their way to the freedom of darkness through plugs of goo and muslin. It was a whole miniature creation, designed in the senseless gooey cores of a Chinese supercomputing gelbrain, and transmuted into reality in a hot broth of undead mechanized protein. This was by far the most amazing phenomenon that Pete had ever witnessed. Pete was accordingly plunged into gloom. Knowledge was power in his world. He knew with leaden certainty that he was taking on far too much voltage for his own good.

Pete was a professional. He could imagine stealing classified military secrets from a superpower, and surviving that experience. It would be very risky, but in the final analysis it was just the military. A rocket base, for instance–a secret Asian rocket base might have been a lot of fun. But this was not military. This was an entire new means of industrial production. Pete knew with instinctive street-level certainty that tech of this level of revolutionary weirdness was not a spy thing, a sports thing, or a soldier thing. This was a big, big money thing. He might survive discovering it. He’d never get away with revealing it.

The thrilling wonder of it all really bugged him. Thrilling wonder was at best a passing thing. The sober implications for the longer term weighed on Pete’s soul like a damp towel. He could imagine escaping this place in one piece, but he couldn’t imagine any plausible aftermath for handing over nifty photographs of thrilling wonder to military spooks on the Potomac. He couldn’t imagine what the powers-that-were would do with that knowledge. He rather dreaded what they would do to him for giving it to them. Pete wiped a sauna cascade of sweat from his neck.

“So I figure it’s either geothermal power, or a fusion generator down there,” said Katrinko.”I’d be betting thermonuclear, given the circumstances.”

The rocks below their busy cleats were a-skitter with bugs: gippers and ghents and kebbits, dismantlers and glue-spreaders and brain-eating carrion disassemblers. They were profoundly dumb little devices, specialized as centipedes. They didn’t seem very aggressive, but it surely would be a lethal mistake to sit down among them. A barnacle thing with an iris mouth and long whipping eyes took a careful taste of Katrinko’s boot. She retreated to a crag with a yelp.

“Wear your mask,” Pete chided. The damp heat was bliss after the skin-eating chill of the Taklamakan, but most of the vents and cracks were spewing thick smells of hot beef stew and burnt rubber, all varieties of eldritch mechano-metabolic byproduct. His lungs felt sore at the very thought of it. Pete cast his foggy spex up the nearest of the carbon-fiber columns, and the golden, glowing, impossibly tempting lights of those starship portholes up above.

Katrinko led point. She was pitilessly exposed against the lacelike girders. They didn’t want to risk exposure during two trips, so they each carried a haul bag. The climb went well at first. Then a machine rose up from wet darkness like a six-winged dragonfly. Its stinging tail lashed through the thready column like the kick of a mule. It connected brutally. Katrinko shot backwards from the impact, tumbled ten meters, and dangled like a ragdoll from her last backup chock.

The flying creature circled in a figure eight, attempting to make up its nonexistent mind. Then a slower but much larger creature writhed and fluttered out of the starry sky, and attacked Katrinko’s dangling haulbag.

The bag burst like a Christmas piñata in a churning array of taloned wings. A fabulous cascade of expensive spy gear splashed down to the hot pools below. Katrinko twitched feebly at the end of her rope. The dragonfly, cruelly alerted, went for her movement. Pete launched a string of flashbangs. The world erupted in flash, heat, concussion, and flying chaff. Impossibly hot and loud, a thunderstorm in a closet. The best kind of disappearance magic: total overwhelming distraction, the only real magic in the world.

Pete soared up to Katrinko like a balloon on a bungee-cord. When he reached the bottom of the starship, twenty-seven heart-pounding seconds later, he had burned out both the smart-ropes. The silvery rain of chaff was driving the bugs to mania. The bottom of the cavern was suddenly a-crawl with leaping mechanical heat-ghosts, an instant menagerie of skippers and humpers and floppers. At the rim of perception, there were new things rising from the depths of the pools, vast and scaly, like golden carp to a rain of fish chow. Pete’s own haulbag had been abandoned at the base of the column. That bag was clearly not long for this world.

Katrinko came to with a sudden winded gasp. They began free-climbing the outside of the starship. It surface was stony, rough and uneven, something like pumice, or wasp spit. They found the underside of a monster porthole and pressed themselves flat against the surface. There they waited, inert and unmoving, for an hour. Katrinko caught her breath. Her ribs stopped bleeding. The two of them waited for another hour, while crawling and flying heat-ghosts nosed furiously around their little world, following the tatters of their programming. They waited a third hour. Finally they were joined in their haven by an oblivious gang of machines with suckery skirts and wheelbarrows for heads. The robots chose a declivity and began filling it with big mandible trowels of stony mortar, slopping it on and jaw-chiseling it into place, smoothing everything over, tireless and pitiless.

Pete seized this opportunity to attempt to salvage their lost equipment. There had been such fabulous federal bounty in there: smart audio bugs, heavy-duty gelcams, sensors and detectors, pulleys, crampons and latches, priceless vials of programmed neural goo. . . . Pete crept back to the bottom of the spacecraft. Everything was long gone. Even the depleted smartropes had been eaten, by a long trail of foraging keets. The little machines were still squirreling about in the black lace of the column, sniffing and scraping at the last molecular traces, with every appearance of satisfaction.

Pete rejoined Katrinko, and woke her where she clung rigid and stupefied to her hiding spot. They inched their way around the curved rim of the starship hull, hunting for a possible weakness. They were in very deep trouble now, for their best equipment was gone. It didn’t matter. Their course was very obvious now, and the loss of alternatives had clarified Pete’s mind. He was consumed with a burning desire to break in.

Pete slithered into the faint shelter of a large, deeply pitted hump. There he discovered a mess of braided rope. The rope was woven of dead and mashed organic fibers, something like the hair at the bottom of a sink. The rope had gone all petrified under a stony lacquer of robot spit. These were climber’s ropes. Someone had broken out here–smashed through the hull of the ship, from the inside. The robots had come to repair the damage, carefully re-sealing the exit hole, and leaving this ugly hump of stony scar tissue.

Pete pulled his gelcam drill. He had lost the sugar reserves along with the haulbags. Without sugar to metabolize, the little enzyme-driven rotor would starve and be useless soon. That fact could not be helped. Pete pressed the device against the hull, waited as it punched its way through, and squirted in a gelcam to follow. He saw a farm. Pete could scarcely have been more astonished. It was certainly farmland, though. Cute, toy farmland, all under a stony blue ceiling, crisscrossed with hot grids of radiant light, embraced in the stony arch of the enclosing hull. There were fishponds with reeds. Ditches, and a wooden irrigation wheel. A little bridge of bamboo. There were hairy melon vines in rich black soil and neat, entirely weedless fields of dwarfed red grain. Not a soul in sight.

Katrinko crept up and linked in on cable. “So where is everybody?” Pete said.

“They’re all at the portholes,” said Katrinko, coughing.

“What?” said Pete, surprised. “Why?”

“Because of those flashbangs,” Katrinko wheezed. Her battered ribs were still paining her. “They’re all at the portholes, looking out into the darkness. Waiting for something else to happen.”

“But we did that stuff hours ago.”

“It was very big news, man. Nothing ever happens in there.”

Pete nodded, fired with resolve. “Well then. We’re breakin’ in.”

Katrinko was way game. “Gonna use caps?”

“Too obvious.”

“Acids and fibrillators?”

“Lost ’em in the haulbags.””Well, that leaves cheesewires,” Katrinko concluded. “I got two.”

“I got six.”

Katrinko nodded in delight. “Six cheesewires! You’re loaded for bear, man!”

“I love cheesewires,” Pete grunted. He had helped to invent them.

Eight minutes and twelve seconds later they were inside the starship. They re-set the cored-out plug behind them, delicately gluing it in place and carefully obscuring the hair-thin cuts. Katrinko sidestepped into a grove of bamboo. Her camou bloomed in green and tan and yellow, with such instant and treacherous ease that Pete lost her entirely. Then she waved, and the spex edge-detectors kicked in on her silhouette. Pete lifted his spex for a human naked-eye take on the situation. There was simply nothing there at all. Katrinko was gone, less than a ghost, like pitchforking mercury with your eyelashes. So they were safe now. They could glide through this bottled farm like a pair of bad dreams.

They scanned the spacecraft from top to bottom, looking for dangerous and interesting phenomena. Control rooms manned by Asian space technicians maybe, or big lethal robots, or video monitors–something that might cramp their style or kill them. In the thirty-seven floors of the spacecraft, they found no such thing.

The five thousand inhabitants spent their waking hours farming. The crew of the starship were preindustrial, tribal, Asian peasants. Men, women, old folks, little kids .The local peasants rose every single morning, as their hot networks of wiring came alive in the ceiling. They would milk their goats. They would feed their sheep, and some very odd, knee-high, dwarf Bactrian camels. They cut bamboo and netted their fishponds. They cut down tamarisks and poplar trees for firewood. They tended melon vines and grew plums and hemp. They brewed alcohol, and ground grain, and boiled millet, and squeezed cooking oil out of rapeseed. They made clothes out of hemp and raw wool and leather, and baskets out of reeds and straw. They ate a lot of carp. And they raised a whole mess of chickens. Somebody not from around here had been fooling with the chickens. Apparently these were super space-chickens of some kind, leftover lab products from some serious long-term attempt to screw around with chicken DNA. The hens produced five or six lumpy eggs every day. The roosters were enormous, and all different colors, and very smelly, and distinctly reptilian.

It was very quiet and peaceful inside the starship. The animals made their lowing and clucking noises, and the farm workers sang to themselves in the tiny round-edged fields, and the incessant foot-driven water pumps would clack rhythmically, but there were no city noises. No engines anywhere. No screens. No media. There was no money. There were a bunch of tribal elders who sat under the blossoming plum trees outside the big stone granaries. They messed with beads on wires, and wrote notes on slips of wood. Then the soldiers, or the cops–they were a bunch of kids in crude leather armor, with spears–would tramp in groups, up and down the dozens of stairs, on the dozens of floors. Marching like crazy, and requisitioning stuff, and carrying stuff on their backs, and handing things out to people. Basically spreading the wealth around. Most of the weird bearded old guys were palace accountants, but there were some others, too. They sat cross-legged on mats in their homemade robes, and straw sandals, and their little spangly hats, discussing important matters at slow and extreme length. Sometimes they wrote stuff down on palm-leaves.

Pete and Katrinko spent a special effort to spy on these old men in the spangled hats, because, after close study, they had concluded that this was the local government. They pretty much had to be the government. These old men with the starry hats were the only part of the population who weren’t being worked to a frazzle. Pete and Katrinko found themselves a cozy spot on the roof of the granary, one of the few permanent structures inside the spacecraft. It never rained inside the starship, so there wasn’t much call for roofs. Nobody ever trespassed up on the roof of the granary. It was clear that the very idea of doing this was beyond local imagination. So Pete and Katrinko stole some bamboo water jugs, and some lovely handmade carpets, and a lean-to tent, and set up camp there. Katrinko studied an especially elaborate palm-leaf book that she had filched from the local temple. There were pages and pages of dense alien script.

“Man, what do you suppose these yokels have to write about?”

“The way I figure it,” said Pete, “they’re writing down everything they can remember from the world outside.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah. Kinda building up an intelligence dossier for their little starship regime, see? Because that’s all they’ll ever know, because the people who put them inside here aren’t giving ’em any news. And they’re sure as hell never gonna let ’em out.”

Katrinko leafed carefully through the stiff and brittle pages of the handmade book. The people here spoke only one language. It was no language Pete or Katrinko could even begin to recognize. “Then this is their history. Right?”

“It’s their lives, kid. Their past lives, back when they were still real people, in the big real world outside. Transistor radios, and shoulder-launched rockets. Barbed-wire, pacification campaigns, ID cards. Camel caravans coming in over the border, with mortars and explosives. And very advanced Sphere mandarin bosses, who just don’t have the time to put up with armed, Asian, tribal fanatics.”

Katrinko looked up. “That kinda sounds like your version of the outside world, Pete.”

Pete shrugged. “Hey, it’s what happens.”

“You suppose these guys really believe they’re inside a real starship?”

“I guess that depends on how much they learned from the guys who broke out of here with the picks and the ropes.”

Katrinko thought about it. “You know what’s truly pathetic? The shabby illusion of all this. Some spook mandarin’s crazy notion that ethnic separatists could be squeezed down tight, and spat out like watermelon seeds into interstellar space. . . . Man, what a come-on, what an enticement, what an empty promise!”

“I could sell that idea,” Pete said thoughtfully. “You know how far away the stars really are, kid? About four hundred years away, that’s how far. You seriously want to get human beings to travel to another star, you gotta put human beings inside of a sealed can for four hundred solid years. But what are people supposed to do in there, all that time? The only thing they can do is quietly run a farm. Because that’s what a starship is. It’s a desert oasis.”

“So you want to try a dry-run starship experiment,” said Katrinko. “And in the meantime, you happen to have some handy religious fanatics in the backwoods of Asia, who are shooting your ass off. Guys who refuse to change their age-old lives, even though you are very, very high-tech.”

“Yep. That’s about the size of it. Means, motive, and opportunity.”

“I get it. But I can’t believe that somebody went through with that scheme in real life. I mean, rounding up an ethnic minority, and sticking them down in some godforsaken hole, just so you’ll never have to think about them again. That’s just impossible!”

“Did I ever tell you that my grandfather was a Seminole?” Pete said.

Katrinko shook her head. “What’s that mean?”

“They were American tribal guys who ended up stuck in a swamp. The Florida Seminoles, they called ’em. Y’know, maybe they just called my grandfather a Seminole. He dressed really funny. . . . Maybe it just sounded good to call him a Seminole. Otherwise, he just would have been some strange, illiterate geezer.”

Katrinko’s brow wrinkled. “Does it matter that your grandfather was a Seminole?”

“I used to think it did. That’s where I got my skin color–as if that matters, nowadays. I reckon it mattered plenty to my grandfather, though. . . . He was always stompin’ and carryin’ on about a lot of weird stuff we couldn’t understand. His English was pretty bad. He was never around much when we needed him.”

“Pete. . . .” Katrinko sighed. “I think it’s time we got out of this place.”

“How come?” Pete said, surprised. “We’re safe up here. The locals are not gonna hurt us. They can’t even see us. They can’t touch us. Hell, they can’t even imagine us. With our fantastic tactical advantages, we’re just like gods to these people.”

“I know all that, man. They’re like the ultimate dumb straight people. I don’t like them very much. They’re not much of a challenge to us. In fact, they kind of creep me out.”

“No way! They’re fascinating. Those baggy clothes, the acoustic songs, all that menial labor. . . . These people got something that we modern people just don’t have any more.”

“Huh?” Katrinko said. “Like what, exactly?”

“I dunno,” Pete admitted.

“Well, whatever it is, it can’t be very important.” Katrinko sighed. “We got some serious challenges on the agenda, man. We gotta sidestep our way past all those angry robots outside, then head up that shaft, then hoof it back, four days through a freezing desert, with no haulbags. All the way back to the glider.”

“But Trink, there are two other starships in here that we didn’t break into yet. Don’t you want to see those guys?”

“What I’d like to see right now is a hot bath in a four-star hotel,” said Katrinko. “And some very big international headlines, maybe. All about me. That would be lovely.” She grinned.

“But what about the people?”

“Look, I’m not ‘people,’ ” Katrinko said calmly. “Maybe it’s because I’m a neuter, Pete, but I can tell you’re way off the subject. These people are none of our business. Our business now is to return to our glider in an operational condition, so that we can complete our assigned mission, and return to base with our data. Okay?”

“Well, let’s break into just one more starship first.”

“We gotta move, Pete. We’ve lost our best equipment, and we’re running low on body fat. This isn’t something that we can kid about and live.”

“But we’ll never come back here again. Somebody will, but it sure as heck won’t be us. See, it’s a Spider thing.” Katrinko was weakening. “One more starship? Not both of ’em?”

“Just one more.”

“Okay, good deal.”

The hole they had cut through the starship’s hull had been rapidly cemented by robots. It cost them two more cheesewires to cut themselves a new exit. Then Katrinko led point, up across the stony ceiling, and down the carbon column to the second ship. To avoid annoying the lurking robot guards, they moved with hypnotic slowness and excessive stealth. This made it a grueling trip.

This second ship had seen hard use. The hull was extensively scarred with great wads of cement, entombing many lengths of dried and knotted rope. Pete and Katrinko found a weak spot and cut their way in.

This starship was crowded. It was loud inside, and it smelled. The floors were crammed with hot and sticky little bazaars, where people sold handicrafts and liquor and food. Criminals were being punished by being publicly chained to posts and pelted with offal by passers-by. Big crowds of ragged men and tattooed women gathered around brutal cockfights, featuring spurred mutant chickens half the size of dogs. All the men carried knives.

The architecture here was more elaborate, all kinds of warrens, and courtyards, and damp, sticky alleys. After exploring four floors, Katrinko suddenly declared that she recognized their surroundings. According to Katrinko, they were a physical replica of sets from a popular Japanese interactive samurai epic. Apparently the starship’s designers had needed some pre-industrial Asian village settings, and they hadn’t wanted to take the expense and trouble to design them from scratch. So they had programmed their construction robots with pirated game designs.

This starship had once been lavishly equipped with at least three hundred armed video camera installations. Apparently, the mandarins had come to the stunning realization that the mere fact that they were recording crime didn’t mean that they could control it. Their spy cameras were all dead now. Most had been vandalized. Some had gone down fighting. They were all inert and abandoned. The rebellious locals had been very busy. After defeating the spy cameras, they had created a set of giant hullbreakers. These were siege engines, big crossbow torsion machines, made of hemp and wood and bamboo. The hullbreakers were starship community efforts, elaborately painted and ribboned, and presided over by tough, aggressive gang bosses with batons and big leather belts.

Pete and Katrinko watched a labor gang, hard at work on one of the hullbreakers. Women braided rope ladders from hair and vegetable fiber, while smiths forged pitons over choking, hazy charcoal fires. It was clear from the evidence that these restive locals had broken out of their starship jail at least twenty times. Every time they had been corralled back in by the relentless efforts of mindless machines. Now they were busily preparing yet another breakout.

“These guys sure have got initiative,” said Pete admiringly. “Let’s do ’em a little favor, okay?”

“Yeah?”

“Here they are, taking all this trouble to hammer their way out. But we still have a bunch of caps. We got no more use for ’em, after we leave this place. So the way I figure it, we blow their wall out big-time, and let a whole bunch of ’em loose at once. Then you and I can escape real easy in the confusion.”

Katrinko loved this idea, but had to play devil’s advocate. “You really think we ought to interfere like that? That kind of shows our hand, doesn’t it?”

“Nobody’s watching any more,” said Pete. “Some technocrat figured this for a big lab experiment. But they wrote these people off, or maybe they lost their anthropology grant. These people are totally forgotten. Let’s give the poor bastards a show.”

Pete and Katrinko planted their explosives, took cover on the ceiling, and cheerfully watched the wall blow out. A violent gust of air came through as pressures equalized, carrying a hemorrhage of dust and leaves into interstellar space. The locals were totally astounded by the explosion, but when the repair robots showed up, they soon recovered their morale. A terrific battle broke out, a general vengeful frenzy of crab-bashing and sponge-skewering. Women and children tussled with the keets and bibbets. Soldiers in leather cuirasses fought with the bigger machines, deploying pikes, crossbow quarrels, and big robot-mashing mauls.

The robots were profoundly stupid, but they were indifferent to their casualties, and entirely relentless.The locals made the most of their window of opportunity. They loaded a massive harpoon into a torsion catapult, and fired it into space. Their target was the neighboring starship, the third and last of them.

The barbed spear bounded off the hull. So they reeled it back in on a monster bamboo hand-reel, cursing and shouting like maniacs. The starship’s entire population poured into the fight. The walls and bulkheads shook with the tramp of their angry feet. The outnumbered robots fell back.

Pete and Katrinko seized this golden opportunity to slip out the hole. They climbed swiftly up the hull, and out of reach of the combat. The locals fired their big harpoon again. This time the barbed tip struck true, and it stuck there quivering. Then a little kid was heaved into place, half-naked, with a hammer and screws, and a rope threaded through his belt. He had a crown of dripping candles set upon his head.

Katrinko glanced back, and stopped dead. Pete urged her on, then stopped as well. The child began reeling himself industriously along the trembling harpoon line, trailing a bigger rope. An airborne machine came to menace him. It fell back twitching, pestered by a nasty scattering of crossbow bolts. Pete found himself mesmerized. He hadn’t felt the desperation of the circumstances, until he saw this brave little boy ready to fall to his death. Pete had seen many climbers who took risks because they were crazy. He’d seen professional climbers, such as himself, who played games with risk as masters of applied technique. He’d never witnessed climbing as an act of raw, desperate sacrifice.

The heroic child arrived on the grainy hull of the alien ship, and began banging his pitons in a hammer-swinging frenzy. His crown of candles shook and flickered with his efforts. The boy could barely see. He had slung himself out into stygian darkness to fall to his doom.

Pete climbed up to Katrinko and quickly linked in on cable.

“We gotta leave now, kid. It’s now or never.”

“Not yet,” Katrinko said. “I’m taping all this.”

“It’s our big chance.”

“We’ll go later.” Katrinko watched a flying vacuum cleaner batting by, to swat cruelly at the kid’s legs. She turned her masked head to Pete and her whole body stiffened with rage. “You got a cheesewire left?”

“I got three.”

“Gimme. I gotta go help him.”

Katrinko unplugged, slicked down the starship’s wall in a daring controlled slide, and hit the stretched rope. To Pete’s complete astonishment, Katrinko lit there in a crouch, caught herself atop the vibrating line, and simply ran for it. She ran along the humming tightrope in a thrumming blur, stunning the locals so thoroughly that they were barely able to fire their crossbows. Flying quarrels whizzed past and around her, nearly skewering the terrified child at the far end of the rope. Then Katrinko leapt and bounded into space, her gloves and cleats outspread. She simply vanished. It was a champion’s gambit if Pete had ever seen one. It was a legendary move.

Pete could manage well enough on a tightrope. He had experience, excellent balance, and physical acumen. He was, after all, a professional. He could walk a rope if he was put to the job. But not in full climbing gear, with cleats. And not on a slack, handbraided, homemade rope. Not when the rope was very poorly anchored by a homemade pig-iron harpoon. Not when he outweighed Katrinko by twenty kilos. Not in the middle of a flying circus of airborne robots. And not in a cloud of arrows. Pete was simply not that crazy any more. Instead, he would have to follow Katrinko the sensible way. He would have to climb the starship, traverse the ceiling, and climb down to the third starship onto the far side. A hard three hours’ work at the very best–four hours, with any modicum of safety. Pete weighed the odds, made up his mind, and went after the job. Pete turned in time to see Katrinko busily cheesewiring her way through the hull of Starship Three.

A gout of white light poured out as the cored plug slid aside. For a deadly moment, Katrinko was a silhouetted goblin, her camou useless as the starship’s radiance framed her. Her clothing fluttered in a violent gust of escaping air. Below her, the climbing child had anchored himself to the wall and tied off his second rope. He looked up at the sudden gout of light, and he screamed so loudly that the whole universe rang. The child’s many relatives reacted by instinct, with a ragged volley of crossbow shots. The arrows veered and scattered in the gusting wind, but there were a lot of them. Katrinko ducked, and flinched, and rolled headlong into the starship. She vanished again. Had she been hit?

Pete set an anchor, tied off, and tried the radio. But without the relays in the haulbag, the weak signal could not get through. Pete climbed on doggedly. It was the only option left. After half an hour, Pete began coughing. The starry cosmic cavity had filled with a terrible smell. The stench was coming from the invaded starship, pouring slowly from the cored-out hole. A long-bottled, deadly stink of burning rot.